Russia Warns Norway of Retaliation Over Fishing Companies Ban: “Must Be Taken Seriously”

Russia reacts strongly to the vessels of its biggest fisheries companies, Norebo JSC and Murman Seafood, losing access to fisheries in Norway's economic zone and to Norwegian ports. Here is a Russian trawler docked in Båtsfjord, Northern Norway. (Archive photo: Joachim Kohler, CC BY-SA 4.0)

"The fisheries cooperation between Norway and Russia has survived several previous crises, but none can be compared to the situation we are currently facing," says Anne-Kristin Jørgensen, Senior Researcher at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute.

In July, Norway joined the EU's sanctions against the Russian fishery companies Norebo JSC and Murman Seafood.

This entails that vessels from the two companies lose access to Norwegian ports and territorial waters, as well as not having their licence to fish in the Norwegian economic zone renewed.

The Norwegian government referred to these companies being "part of a Russian state-sponsored surveillance campaign and intelligence activity targeting critical underwater infrastructure in Norwegian and allied maritime areas."

Russia warns of retaliatory measures, Russian state news agency TASS reported last week.

"If the Norwegian side does not reconsider its position within a month, Russia will close its exclusive economic zone for Norwegian fishing vessels. Furthermore, fisheries and the allocation of quotas in the open waters in the Barents and Norwegian Seas will carried out on the basis of Russian national interests," said Ilya Shestakov, Head of the Federal Agency for Fishery in Russia.

Significance in practice

"The Russian threats must be taken seriously," writes Anne-Kristine Jørgensen, Senior Researcher at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI), in an e-mail to High North News.

What does it entail if the measures are put into practice?

"It is not the worst thing if Norwegian fishing vessels lose access to the Russian economic zone. Not many Norwegian vessels fish there now," replies Jørgensen and continues:

"Setting their own quotas, however, is of greater significance. If the parties do not reach a quota agreement for next year, the consequence will be that Norway and Russia must set their own quotas in their own waters."

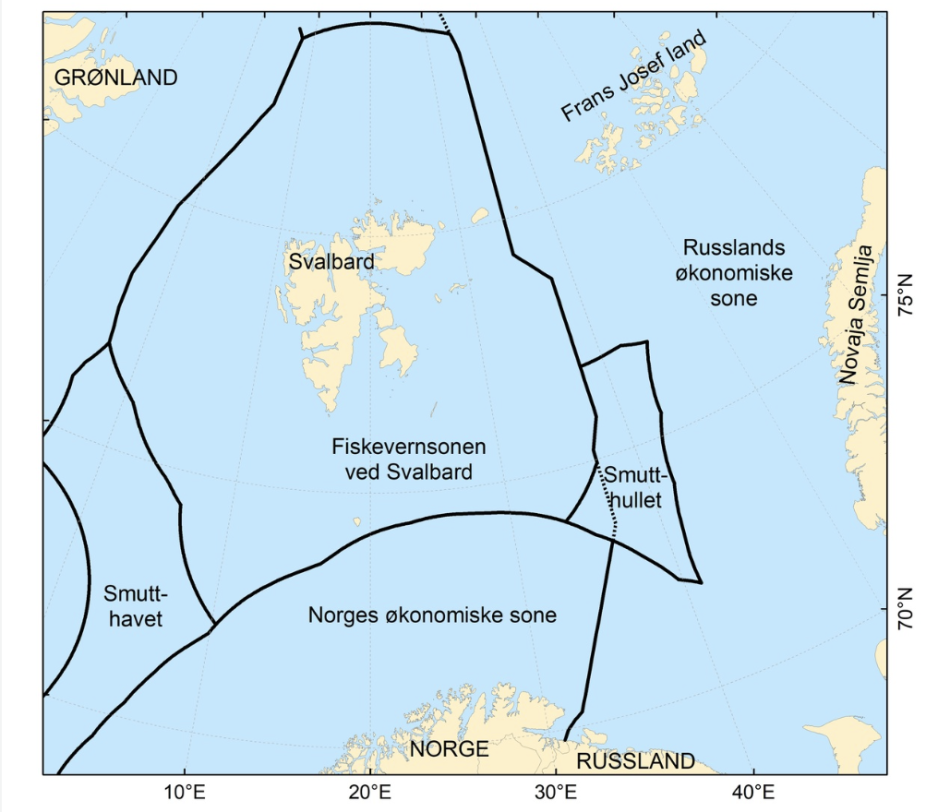

"When the Russians state that they want to fish and set one-sided quotas in 'open waters in the Barents and Norwegian Seas,' that could be a signal of them wanting to continue fishing by Svalbard even if there is no quota agreement for 2026, and they lose access to the Norwegian economic zone. As is known, the Russians do not acknowledge the Svalbard Fisheries Protection Zone, and they have occasionally advocated for this area to be considered open waters."

The Norwegian-Russian fishery cooperation in short

· Norway and Russia have cooperated on the management of shared fish stocks in the Barents Sea since the 1970s.

· The Joint Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Commission sets annual quotas for cod, haddock, capelin, Atlantic redfish, and Greenland halibut.

· The quota advice has normally been anchored in the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES). ICES suspended Russia in March 2022 due to its war in Ukraine, and the quota advice has since been provided by a Norwegian-Russian research group.

A deadlock that could be hard to escape.

Unparalleled

In the bigger picture, the long-term Norwegian-Russian fisheries cooperation is at stake.

"Both Norway and Russia have strong interests in keeping the cooperation afloat, and both parties have warned against the consequences for the stock if it breaks down. However, we are in a 'deadlock' that could be hard to escape," the FNI researcher points out.

"The fisheries cooperation between Norway and Russia has survived several previous crises, but none can be compared to the situation we are currently facing. Should the worst happen – that no fisheries agreement for 2026 is reached this autumn – it will probably not entail any immediate danger of fish stocks collapsing. It would still be a serious situation, given that the stocks are at such a low level."

The decline of the cod stock

· Norway and Russia manage the world's largest cod stock, the Northeast Arctic cod, in the Barents Sea.

· Since a historic peak in 2013, the spawning stock of cod has been in annual decline.

· This has led to the quota advice and the set quota being lowered by 20 percent each year from 2021 to 2024, and reduced even further in 2025: For this year, the scientists recommended a decrease of 31 percent; Norway and Russia reduced the quota by 25 percent.

· The scientists assess the situation for cod to be still serious and recommend a quota for 2026 that is 21 percent lower than the set quota for this year. This quota advice is the lowest since 2002.

The Northeast Arctic cod, also known as skrei, in the Barents Sea. (Photo: Joachim S. Müller)

On the Norwegian side, we want to continue the cooperation on fisheries management in the Barents Sea.

Extraordinary meeting

Halvard Wensel, Communications Adviser in the Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries. (Photo: NFD)

Last Tuesday, the Joint Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Commission held an extraordinary session on Russia's initiative.

The meeting, held digitally, took place against the backdrop of the Norwegian decision not to renew the aforementioned companies' licence for fisheries in the Norwegian economic zone, informs Communications Adviser Halvard Wensel in the Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries.

"The discussion will continue in a new meeting between the parties. On the Norwegian side, we want to continue the cooperation on fisheries management in the Barents Sea," writes Wensel in an e-mail to HNN.

Different reaction

Shestakov's statement and Russia's call for an extraordinary session constitute a strong Russian reaction that differs from previous ones, the FNI researcher assesses.

During the fisheries negotiations over the past three years, Russia has threatened to put quota agreements on hold if Norway further expands the port ban on Russian fishing vessels.

At the same time, this threat has been made as a point in the negotiation protocols, and with a certain reservation in the form of the Russian part 'reserving the right to suspend this protocol,' Jørgensen points out.

"This phrasing opened for the possibility to react this way, not necessarily having to do so. Back then, I interpreted it as not wanting to tie themselves down, because it would not be in Russia's interest to withdraw. They also did not make a big deal of it at home, and the matter received limited attention in Russian media."

Perceived breach of agreement

Now the FNI researcher notes that the Russian threats have been conveyed without reservations and believes that this is related to two factors in particular.

"Firstly, Russia considers it a breach of agreement that Norebo and Murman Seafood lose access to the Norwegian economic zone," states Jørgensen and continues:

"Mutual access to fisheries in each other's zones is laid down as a principle in the Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Agreement of 1976 – one of the two agreements that form the basis for the fisheries cooperation. Although only the sanctioned companies lose this access, Russia believes that Norway's actions violate this agreement."

The new sanctions likely have far greater economic consequences.

Economic consequences

Russia also reacts this strongly because sanctions against the fisheries companies would have a significant economic impact, according to the FNI researcher.

"The new sanctions likely have far greater economic consequences than the partial port ban, which was already implemented," writes Jørgensen.

In the fall of 2022, the Norwegian government decided that Russian fishing vessels could only dock in Kirkenes, Båtsfjord and Tromsø, and that they were to be controlled upon calling.

Last summer, restrictions were also implemented on how long and where they can stay in these ports. The controls were also reinforced.

"Although the port ban has made things a bit more difficult for the Russians, it has been of great significance that the three most important ports for the landing of fish have remained open. The fact that two of the largest fisheries companies now lose both access to fisheries in the Norwegian economic zone and to Norwegian ports is more serious," she argues.

The Barents Sea with borders between Norway and Russia's economic zones. (Map: the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research)

Major export companies are important taxpayers.

State economy impact

Jørgensen refers to statements made by Norebo Representative Vladimir Grigoriev to the Russian news agency Interfax on August 20th.

Grigoriev says that Norebo and Murman Seafood account for 40 percent of the Russian cod and haddock catches in the North, and that the sanctions will impose major additional costs on them.

He also points out that the daily operating costs for a medium-sized vessel that the company currently operates in northern waters are estimated at $20,000, and that the transit time from fishing grounds in the Barents Sea to Murmansk is three days, compared to eight hours to a Norwegian port.

"I cannot say whether these figures are correct, but there is no doubt that the Russians' newest vessels are expensive to operate, and that is one of many reasons it is economically beneficial for the Russian companies to deliver fish in Norway," notes the FNI researcher and continues:

"Major export companies are important taxpayers. This affects not only the companies but also the Russian economy. In recent years, after Russia's full-scale war against Ukraine, companies in export industries such as fisheries have paid an additional export tax on top of other taxes and duties."