Canada Makes Substantial Step in Arctic Territory Delimitation, Submits Claim Which Includes North Pole

Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard speaks at an event in British Columbia. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans contributed to the collection of data for Canada’s 2,100-page continental shelf submission to the United Nations. (Photo: Government of British Columbia)

After years of research, the Canadian government submitted a 2100-page report to the United Nations regarding its Arctic continental shelf delimitation.

After more than a decade of research, Canada took a significant step in defining its territorial map and further staking its claim in the Arctic, when it filed a submission with the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf at the United Nations in New York City on Thursday May 23.

The 2,100 page document was submitted by Pamela Goldsmith-Jones, parliamentary secretary to the minister of foreign affairs, on behalf of Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland. The move was touted by the government as a critical step in asserting Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic, and “serving the interests” of all people, including Indigenous groups.

“Canada is a proud ocean nation. The filing of the Arctic Ocean continental shelf submission is a major milestone in delivering on the government’s priority to define the outer limits of Canada’s continental shelf. Today we are taking a major step forward in ensuring Canada’s Arctic sovereignty,” Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard said of the submission.

The research was based on 17 expeditions to the Arctic, in which data was collected and interpreted by scientists from Natural Resources Canada (Geographical Survey of Canada), and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Canadian Hydrographic Service). Other agencies and actors, including the territorial governments of Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard, Defence Research and Development Canada, Indigenous peoples, and the Department of National Defence, contributed to the data collection. Additionally, the Canadian government collaborated with Denmark, Sweden, and the United States in the form of join surveys and other scientific work. A press release from the Canadian government states that the efforts have “exponentially increased the scientific knowledge of the Arctic Ocean and opened a new chapter in the understanding of its history, geology and geomorphology.” The resulting claim is over 1.2 million square kilometres of seabed and subsoil, including the North Pole. If the submission is approved, Canada will have exclusive rights to resources underneath this water.

The continental shelf debate is a relatively recent phenomenon. Until the start of the new millennium, both the North Pole and much of the Arctic Ocean were considered neutral territory. However, as climate change has caused ice to recede and opened up new economic opportunities in this region, a number of countries have made claims to territory in the north.

Under the United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a state with coastal territory has an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) which extends 200 nautical miles (or 370 kilometres) beyond its shores, giving it extended territory in which to conduct economic activity. However, a state may make a scientifically-substantiated claim to the continental shelf underneath the water and argue that this further extension should be considered part of its territory as well. If the state’s proposal is confirmed by the United Nations, the state can claim exclusive economic rights to the resources in (and under) its continental shelf area.

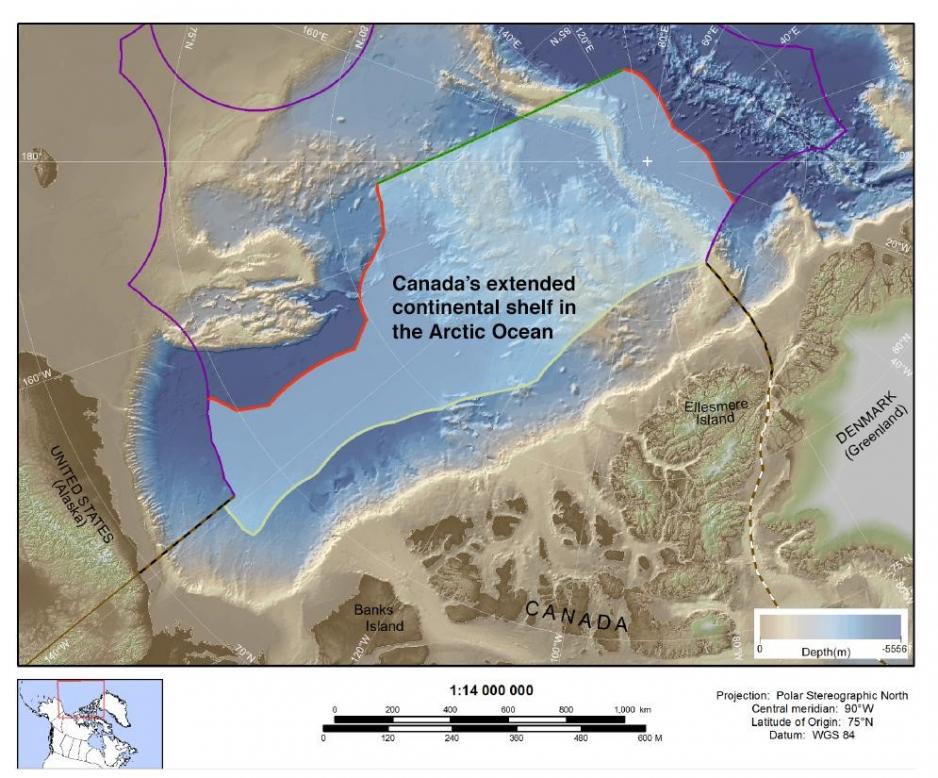

Map provided by Government of Canada

So far, Norway, Denmark, Canada, and Russia have worked on Arctic continental shelf claims, while the United States has signed but not ratified the UNCLOS agreement. Norway submitted a continental shelf proposal in 2006, and Denmark followed suit in 2014. Russia submitted a claim in 2001, but in 2002 the UN Commission recommended further research. Since then, the Russian team has made several additional data submissions to its proposal, and has argued that the North Pole also falls under their continental shelf delimitation. Their claim has been under evaluation by the UN Commission since 2016. Thus, Denmark, Russia, and Canada have all argued that the North Pole should be under their jurisdiction, BBC News reported, and there are multiple other disputed areas in the proposals.

“International recognition of the outer limits of Canada’s extended continental shelf is vital to ensuring our sovereignty and protecting our national interests,” said Amarjeet Sohi, Canada’s minister of natural resources on Thursday. “We are proud to support Canada’s Arctic Ocean submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, supported by science and evidence, reaffirming our government’s commitment to furthering Canada’s leadership in the Arctic.”

However, there is still a long way to go until Canada’s claim to the Arctic territory is approved. The Canadian government itself has said this may take up to 10 years, and “additional time may be needed to delimit boundaries in areas where Canada’s continental shelf overlaps with neighbouring states.”

According to Andreas Osthagen, a researcher at the Fridtjof Nansens Institute in Norway, the claim to the North Pole is about national identity and symbolism for northern nations more than the quest for natural resources.

“There is very little to fight over,” Osthagen said in a phone interview on Saturday. Research shows that it is unlikely there are many resources directly underneath the North Pole, and Arctic countries are more keen to develop resources closer to their shores for logistical reasons.

Given that the United States has not even ratified the convention, and seems unlikely to do so in the future, it is likely that this debate over the North Pole may become a frozen or “dormant” dispute for many years, Osthagen said. “There is nothing to suggest this is a pressing issue,” he said. “Without the presence of resources, there is not a big impetuous to care about the delimitation of the North Pole.”

Nonetheless, it is significant that these states are willing to negotiate the delimitation at the United Nations. “There is value in that the countries have set out to adhere to the Law of the Sea,” said Osthagen. Russia, which is normally seen as an aggressor in the north, has explicitly stated that they’d try to find a solution through negotiations within international bodies, He added. Osthagen also noted that Russia has “never renegaded” from the Law of the Sea, possibly because it is one of the biggest benefactors from the agreement. It seems likely that Canada will cooperate with any UN ruling as well, “given Canada’s history as an international global actor that tries to play by the rules.” Therefore, Osthagen believes that the “race for the Arctic” will not become a hot conflict, given that all parties seem poised to accept the ruling of the UN, whenever it comes. Given that it took Norway and Russia over four decades to negotiate the Barents Sea delimitation, it appears that these discussions are just getting started.