You can’t own the North Pole

- No, the purpose is not to take over the North Pole, asserts Danish Christian Marcussen to his audience during High North Dialogue. You can't own the North Pole.

Marcussen is a geophysicist, as well as senior advisor and project leader for the Greenland segment of the Continental Shelf Project in Denmark. During the High North Dialogue conference, Marcussen explained the technical and legal background to Denmark’s submission, regarding definition of territorial boundaries, to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

Resources in focus

PhD candidate Gunnar Sander at UiT Norway’s Arctic University puts it bluntly;

-

Dividing the orange

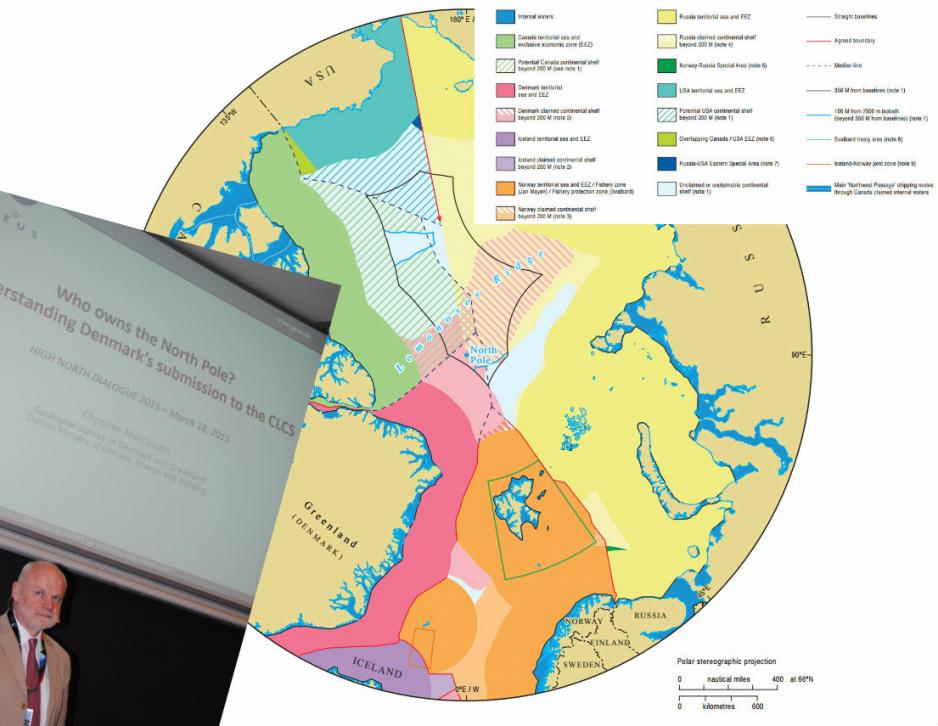

There are, however, overlapping interests in the territories that Denmark has expressed a desire to “take over”. Theoretically speaking, it is not impossible for several states to possess continental plates that overlap.

-

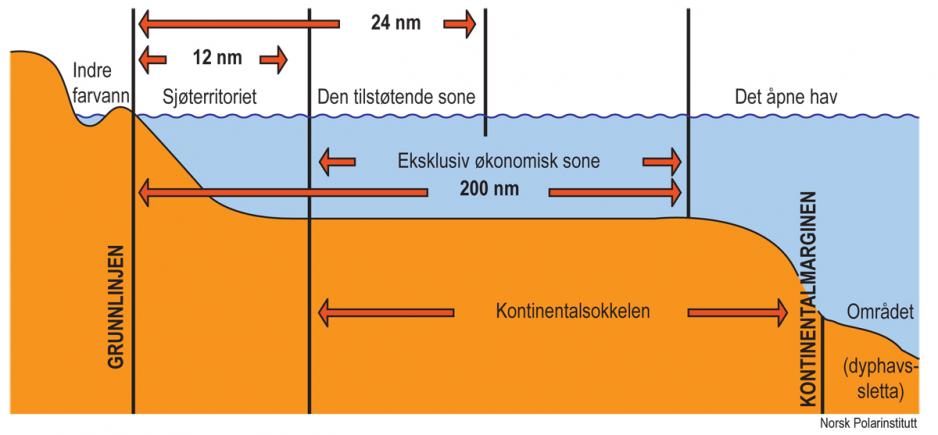

The illustration below shows how off-coastal zones are defined by the United Nations.

Many can be right

Countries submit data to CLCS, as Denmark did in December 2014, after which CLCS checks the figures in relation to criteria laid out in the Law of the Sea.

Russia and Canada are expected to submit territorial claims that overlap parts of the claim sent in by Denmark and, theoretically speaking, all of them can be “right”.

Negotiation is the key

-

The Commission can, therefore, allocate the rights to a particular area to several states. Coastal states will have to negotiate these overlaps. According to Sander, the same can problem can arise between states that face one another, eg. Russia <-> Canada and Russia <-> Greenland.

Recommendations only

-

-

International tribunal

-

However, the dispute provisions do provide for a specific tribunal. In such a case, one or more states must summon the relevant coastal state to the international tribunal.

Will remain “common”

According to Gunnar Sander, questions about extended continental shelves will not have any ramifications for the status of the high seas.

-

A long way to go

The Danish senior advisor, Christian Marcussen, is also aware that there will come no recommendations from the Commission in the next few weeks, possibly not for years.

-

Translation by Sarah Kathleen Evans, UiN.