Urgent Calls for IMO to Cut Black Carbon Emissions as Arctic Shipping Traffic Doubles

Cargo shipping leaving port with plume of black smoke coming out of its smoke stack. (Source: Roberto Venturini under CC BY 2.0)

Despite a partial ban on heavy fuels oils enacted in 2024 black carbon emissions from Arctic shipping continue to grow. A new report now calls for urgent action by the IMO to curb the harmful particulates and switch to cleaner, less polluting fuels.

A new report by Pacific Environment sheds new light on the impact of black carbon emissions on the Arctic region and local communities.

With shipping traffic doubling over the past decade the issue is becoming increasingly urgent, with the environmental group calling for immediate action by the UN’s shipping body, the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

“Despite more than a decade and a half of debate, U.N.’s maritime shipping body the IMO continues to ignore the simple solution: require ships to immediately switch to cleaner fuels when operating in the Arctic. Despite technical assessments and calls for voluntary measures at the IMO, black carbon emissions from Arctic shipping continue to grow unchecked,” says Kay Brown, Arctic policy director, Pacific Environment.

Yet, technical and economically feasible solutions are at hand through switching to fuels suitable for the polar environment. The report calls on the IMO to mandate the use of fuels with a smaller black carbon footprint, such as low-sulfur fuel oil fuels, marine gas oil, or liquefied natural gas.

Existing rules riddled with loopholes

Under existing IMO regulations for most vessels the use of Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO), a tar-like, thick and relatively cheap oil commonly used in shipping around the world, remains permissible in the Arctic until 2029.

An initial ban for HFO took effect in mid-2024, but it is riddled with extensive loopholes allowing the fuel’s continued use in most cases until close to the end of the decade.

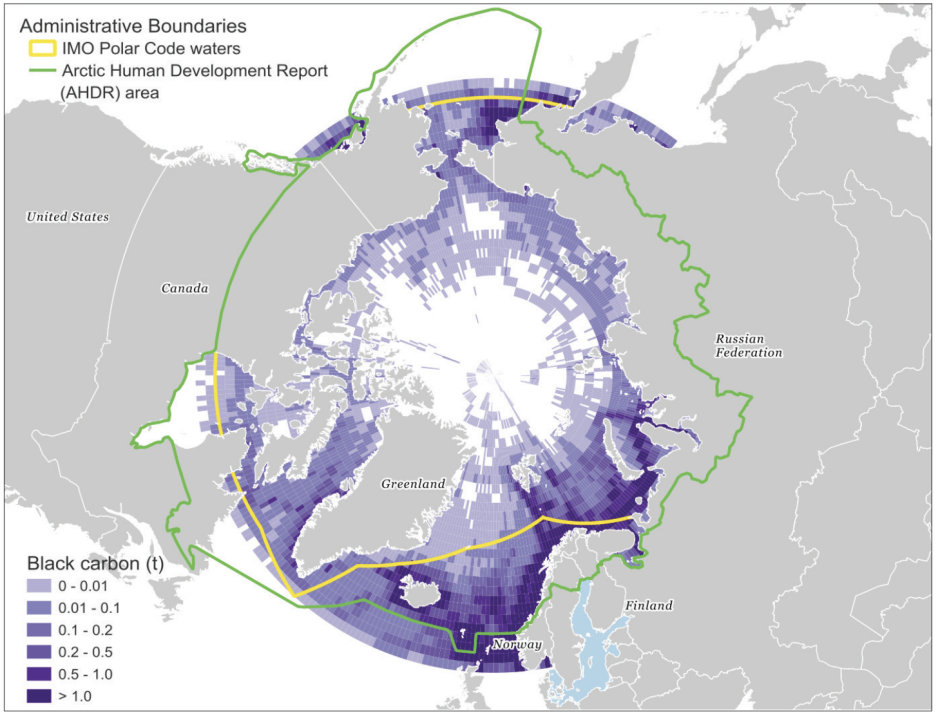

Black carbon emissions across the Geographic Arctic in 2021. Map designed by Liudmila Osipova. (Source: Osipova & Gore (2025) via Pacific Environment)

Black carbon, or soot, emitted from the smoke stacks of vessels passing through the Arctic, constitutes a growing issue for the region’s environment and global climate stability at large.

The particles making up black carbon settle on Arctic snow and ice dangerously accelerating local melting and driving the regional warming trend.

More shipping - more emissions

Over the past decade the Arctic region has seen a more than doubling of shipping traffic based on vessel distance traveled.

The Arctic Council’s latest Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) Arctic shipping status report shows the cumulative distance of vessels traveled increasing from 6.51 million nautical miles in 2013 to 12.7 million in 2024.

The number of individual vessels entering the Arctic also jumped 37 percent to 1,781 in 2024.

Both the atmosphere and the Arctic landscape below absorbs more solar radiation

Amplified warming

Globally efforts to reduce carbon dioxide and methane emissions are at the forefront, but regionally in the Arctic black carbon has an outsized impact. Per unit of mass, black carbon has a warming potential 1,500 times greater than CO2.

It leads to both the atmosphere and the Arctic landscape below absorbing more solar radiation, reducing the region’s reflective albedo, and amplifying warming.

Black carbon also directly affects the health and wellbeing of Arctic Indigenous and coastal communities. Inhalation of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is tied to increased risk of cardiovascular disease and respiratory illness.

Led the way

Sustained efforts have been made across the EU and Europe to systematically reduce these types of emissions from land-based transportation systems, like cars and trucks in city environments.

Norway has led the way by banning the use and carriage of HFO throughout the waters of Svalbard substantially reducing black carbon emissions around the archipelago.

The next opportunity for the IMO to enact stricter rules comes in February 2026 during a meeting of the Sub-Committee on Pollution Prevention and Response (PPR).