Researcher on New Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Agreement: “Shows How Important the Cooperation Is for Both Parties”

Geir Hønneland, Senior Researcher at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute and professor at the High North Center for Business and Governance, Nord University.

Neither Russia nor Norway seemed to have played on the current tense situation in the fisheries negotiations. In the agreement for 2023, they are following the researchers' quota advice in an exemplary manner. A solid sign of the cooperation's great value for both parties, says senior researcher.

On Tuesday, it became known that Norway and Russia have agreed on next year's fisheries in the Barents Sea, despite the fact that the negotiations have taken place with the Ukraine war and with an increasingly more tense security situation as a backdrop.

Geir Hønneland, one of Norway's leading researchers on Norwegian-Russian fisheries cooperation, shares his views on the new agreement with High North News.

"The key here is that Norway and Russia have actually agreed on a quota agreement for 2023 and that they have set the total quotas according to the scientific recommendations. They have also stayed within the Joint Norwegian-Russian Commission's own negotiation framework on quota determination for the various fish stocks," says the senior researcher at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI) and continues:

"None of them seems to have exploited the tense situation in order to put forward special demands or challenge the other party unnecessarily, like demanding total quotas that exceed the researcher's advice. Or at least, such demands have not come to fruition, and the parties have stayed loyal to the negotiation framework."

That is striking in today's situation, Hønneland points out.

"That they have not even tried to push the limits of these recommendations, as have been done on a number of previous occasions, almost has a symbolic meaning. It can be interpreted as a concrete expression of how much both countries value this cooperation."

Access to Norwegian ports is hardly that important.

Empty threats

When the new fisheries agreement was presented, it was also revealed that Russia had stated that it could be put on hold if Norway chooses to further restrict access to Norwegian ports for Russian fishing vessels. After a restriction earlier in October, Russian fishing vessels can only dock in Kirkenes, Båtsfjord, and Tromsø, in Northern Norway, and they will be controlled upon arrival.

Specifically, this Russian message was relayed in the Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries' press release about the agreement – which is the most important and largest bilateral fisheries agreement that Norway has.

Russia is unlikely to put this verbal bargaining chip into practice when they have so much to lose by doing so, believes the FNI researcher.

"I would like to emphasize that Russia has a fundamental economical interest in maintaining the bilateral management regime in the Barents Sea. This is what provides them access to the big fish, which are mainly found in Norwegian waters. Without the agreement with Norway, they would be relegated to fishing for small fish in the rearing areas east in the Barents Sea. I therefore perceive these as empty threats from the Russian side," he says.

Hønneland further elaborates on why scrapping the arrangement for 2023 seems unrealistic:

"Access to Norwegian ports is hardly that important, that the Russians would sacrifice the bilateral regime which secures them such a large share of the cod quota in the Barents Sea; on a purely biological basis, the Russians should have had less than the 50 percent they have now [of the combined Norwegian-Russian share of the total quota, the rest goes to third countries, ed.note]."

This year's negotiations in the Joint Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Commission (from 17 to 24 October) have also taken place digitally, previously due to the COVID pandemic and now due to Russian warfare in Ukraine. Here from the signing of the fisheries agreement for 2022 by the leaders of the countries’ negotiating delegations. (Photo: NFD)

We are not there yet.

Tongue on the scale

According to Hønneland, it is not unusual for points of contention to be raised during fisheries negotiations within the section for questions.

"Both parties' views on the matter are then referred to in the protocol, which has worked well for many years. If the protocol or the negotiation framework were to be put aside, it would have to be by order of the highest levels of Russian politics, in a situation where security policy differences trump economic interests. We are not there yet."

"When it comes to the Norwegian government's delivery of the Russian statement in the press release from the commission meeting, one could speculate if the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, which has been reluctant to close Norwegian ports, wants to show that the Russians are threatening with stronger measures if Norway were to close any more ports," he says.

The die could still be cast

If it were to go as far as the security policy conflict becoming overshadowing and the specific agreement for next year falls through, the consequences will not necessarily be very dramatic in the short term, the researcher believes.

"Because there is both scientific agreement between Norwegian and Russian researchers on how large the fish quotas should be, and also a political agreement between the parties on following the scientific recommendations," says Hønneland.

In such a case, one or both parties might have operated with somewhat higher quotas each, but a prior common basis would probably encourage restraint.

For the Russians, it is far more important to have continued access to the Norwegian zone than ports.

The elephant in the room

However, the question of fishing access in each other's exclusive economic zones may present troubled waters, he points out.

"That is the elephant in the room. For the Russians, it is far more important to have continued access to the Norwegian zone than Norwegian ports, at least from an economical perspective."

Mutual zone access is the basis for Russian fishers mainly fishing their share of the quota in the western part of the Barents Sea, in the Norwegian economical zone and the fishery protection zone around Svalbard, where, as mentioned, the fish are the largest.

"In the protocol from the commission meeting, the Russians state that they believe the restriction of port calls is a violation of the bilateral agreements from the middle of the 1970s, which form the legal and political basis for the cooperation. Norway flatly rejects this notion and it is quite obvious that these agreements do not say anything about mutual access to port calls," states Hønneland and elaborates:

"In addition to the fact that it is not actually mentioned and can hardly be interpreted in the agreements, it is unreasonable as access to ports was not granted until around 1990. In other words, the parties lived for a decade and a half with the current framework without such access."

It is not in anyone's interest that this management cooperation is broken

The bottom line

Should the overall fishery cooperation break down, with a lack of legal basis for Russian fishing in the Norwegian zone as one of the consequences, the situation might turn sour.

"We would then have a situation in which the Russians would only be allowed to fish in the Russian zone where the fish are very small. This would be very unfortunate for the resource fundament and a situation no one wants. Small fish will give Russian fishers less income and if the fish are not allowed to grow in the Russian zone, we will eventually not have large fish in the Norwegian zone," explains the FNI researcher.

"It is important to remember that such a scenario will also be negative for Norway. Overall, the following is essential: It is not in anyone's interest that this management cooperation is broken and that the parties do not grant access to each other's economic zones," he states.

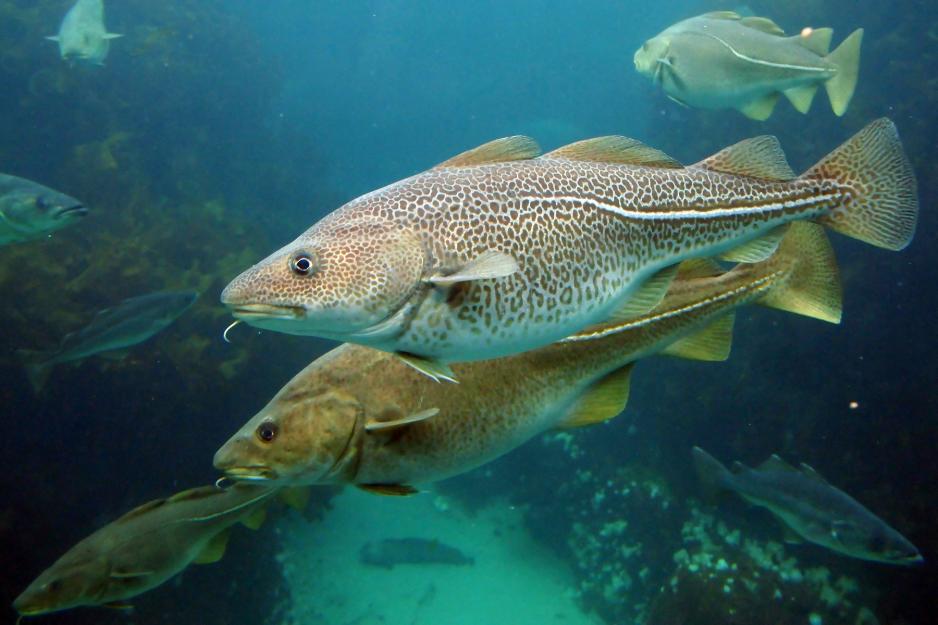

Norway and Russia have cooperated on the management of joint fish stocks – such as the world's largest cod stock, the North East Arctic cod – in the Barents Sea since the 1970s. (Photo: Joachim S. Müller)

Has withstood a blow

The fishery cooperation also constitutes one of the very few sustained areas of contact between Norway and Russia in the wake of the Ukraine war. The FNI researcher outlines how this channel has survived many difficulties:

"The mixed Fisheries Commission has been a very central point of contact between Norway and (Soviet) Russia ever since its establishment nearly 50 years ago – and has functioned through major political ups and downs. It came into being during the Cold War and has functioned through perestroika [economical restructuring, ed.note]. at the end of the Soviet era, as well as during the 1990s chaos and subsequent new austerity measures in Russia, and even after the Russian annexation of Crimea."

"The work around the joint fisheries management has been steadily defying all this, so this collaborative framework has been proven to be sustainable and solid," Hønneland sums up.

A central point of contact that has functioned through major political ups and downs.

One last "outpost"

The fisheries cooperation also seems to have served as a springboard for the significant maritime delimitation treaty for the Barents Sea between Norway and Russia, concluded in 2010.

"In 2009, the Joint Norwegian-Russian Fisheries Commission agreed on a number of new compromises. For example, there was an agreement on the minimum size of mesh in fishing nets, which had been a point of contention for several decades. Then, the delimitation treaty came into place, which was also pure compromise," says the researcher.

After 40 years of negotiations on maritime delimitation between the countries, the previously disputed area in the Barents Sea was divided into two equal parts, for important legal clarity and predictability for both parties.

"Thus, one can at least speculate about whether this stability that the Joint Fisheries Commission provides has contributed to a positive spillover to other political areas as well," says Hønneland and concludes:

"We are now in an extreme situation where almost all other contact between Norway and Russia has been broken, so fisheries cooperation is in a way the last outpost – a last remnant of normality.

Also read

This article was originally published in Norwegian and has been translated by Birgitte Annie Molid Martinussen.