Indigenous Communities ‘Reclaim History’ in Images of Canada’s Arctic

Until recently, many Indigenous people portrayed in early photographs of the Canadian Arctic remained nameless in the federal government’s archives. Project Naming seeks to change that by tapping northern community knowledge.

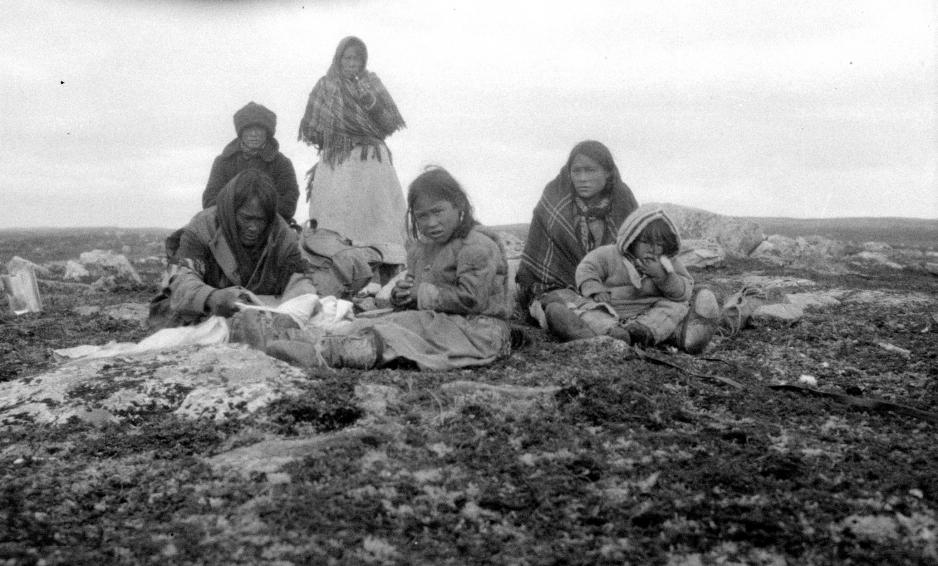

They were referred to simply as Eskimo, native, half-breed or even savage.

For decades, Indigenous peoples in Canada’s northern territories have been photographed and depicted in tens of thousands of images, locked away in the government archives in Ottawa.

And for the most part, the people in those photographs were nameless.

That is, until Project Naming began putting names to the people, places and activities that were captured in the Canadian Arctic.

“I think it’s important in that it gives us the opportunity to reclaim history, by putting names to unidentified individuals,” said Deborah Kigjugalik Webster, a heritage researcher originally from Baker Lake in Nunavut.

Webster curates a project on Inuit special constables who worked in Nunavut with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and she has used the Project Naming database to uncover information about this little-known slice of history.

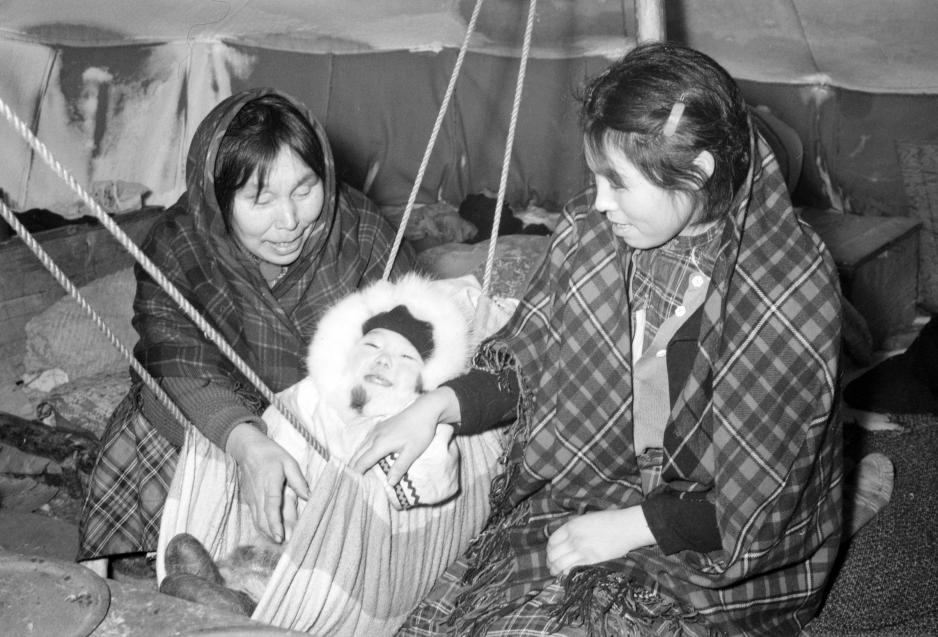

For some Inuit families, this may be the first time they have ever seen some of their ancestors in photographs, while for others, it can reveal information about their loved ones that they never knew.

A family from Baker Lake, for example, was unaware that their ancestor had served as a special RCMP constable in 1945 and 1946, until Webster found his photograph in the Project Naming database.

“They were able to confirm this was his photo, and they had never seen it before, so it was very special,” Webster told Arctic Deeply about the man, whose last name was spelled at least four different ways in the public record.

The RCMP spelled it Oogoocoot, the National Film Board photographer that took the photo spelled it Cogiakuk, and more recently it was spelled both Uqiakut and Ugiaqut.

“When you have an unnamed person, and then being able to put a name to that person, to me that’s very gratifying,” Webster said.

“When someone hasn’t seen their grandfather in an image like that, it’s very touching. It’s important for us to remember our history and know our family history and know our heritage to be a strong people.”

‘Family Photo Albums’ in Ottawa

Project Naming began as a partnership between Library and Archives Canada, the Nunavut Department of Culture, Languages, Elders and Youth, and Nunavut Sivuniksavut, a college program in Ottawa that trains Inuit youth from Nunavut.

But it was really the brainchild of Murray Angus and Morley Hanson, two instructors at the school who began taking their students to the government archives in the 1990s to manually flip through the catalogues of images from the North.

Students would choose an image from their home community or region, which they would enlarge, print and take home at Christmas.

Every year, the students would come back to Ottawa with stories about the fascinating conversations the photographs provoked with community elders, grandparents and other relatives, Angus recalled.

“In the 50s and 60s, most people typically didn’t have a camera, so people up north didn’t tend to have family photo albums. So in fact, the family photo albums for the people of Nunavut were actually stored in vaults down in Ottawa,” he told Arctic Deeply.

The students eventually took dozens of images back to Nunavut on laptops and CDs to show community members, who then shared their knowledge and crafted detailed captions of whom and what they saw.

But digitization is what really tapped into the wider potential of the project.

“That was the key that unlocked the vault for all these photographs because prior to that, people in the North would have to travel down to Ottawa and go to the archives to look for pictures of their own family, if they even knew that those photos existed,” Angus said.

Easily Accessible Online

Since 2002, about 8,000 images have been digitized and almost 2,000 individuals, activities and places have been identified through Project Naming.

But that’s only a fraction of the photographs of Indigenous peoples that fill the library and Archives Canada collections, explained Beth Greenhorn, the manager of Project Naming.

“It’s so, so small, and still there’s even thousands of photos to look through,” Greenhorn said. “Being able to improve the descriptions, describe activities, identify the people, identify the locations, the content and subject in the photos … is a continuing goal for us.”

Some of the earliest images of Inuit, First Nations and Métis in the government archives date back to the late 1850s or 1860s, but most pictures that people have been digitized and identified in were taken between the early 1900s and the 1960s and 1970s.

“The breadth and depth of the collections can be a little overwhelming so very often when people have come to us and they’ve said, ‘I’m from Baker Lake, I’m interested in seeing these photos,’ then … we can put that onto the digitization schedule,” Greenhorn said.

While the project’s initial focus was on Inuit communities in Nunavut, it expanded in 2015 to include Inuit in the Northwest Territories and in Nunavik (northern Quebec) and Labrador, as well as First Nations and Métis communities.

Anyone can look through the Project Naming database online, and search for images according to a person’s name, location, activity, date or the photographer’s name, or by using keywords.

Once an image is found, you can then submit information related to it, including the names of people in the photograph, where it was taken and when, and what is happening in the image.

The information is kept confidential, and it is then added to the database and shared with the public. People can also order physical copies of the images they find in the database.

Sharing Oral Histories

Greenhorn said she sees the project, which will be celebrating its 15th anniversary with a series of events in Ottawa in March, as part of a broader movement in Canada and around the world that is seeking to come to terms with the past.

"For centuries or decades, the North has been seen as this romantic, northern, frozen place where these exotic people live," she said. "I think in some ways this project feeds into this broader change of understanding and correcting some of the past wrongs."

According to Angus, identifying people in the images revealed the importance of family relationships in Inuit culture: a person would often not only be identified by his name, but also as the “husband of, father of [or] son of” other members of that community.

The project also helped bridge a gap between the generations, he said, because Inuit youth would sometimes feel intimidated to approach their elders, often due to a language barrier or their inability to communicate well in Inuktitut.

"It’s very time sensitive, the whole undertaking, because once the current elders have passed on, given the dates on those photographs, no one ever may be able to identify who they are," he said.

"There’s a transfer of oral history that sort of emanated from looking at photographs. From that point on, the young people own those stories, too."

This article originally appeared on Arctic Deeply, and you can find the original here.

For important news about Arctic geopolitics, economy, and ecology, you can sign up to the Arctic Deeply email list.

The author if this article, Jillian Kestler-D’Amours, is a freelance journalist based in Toronto. She previously worked as a staff reporter at The Toronto Star and a web producer at Al Jazeera English.