Russian Exile Artist Transforms the Silence in the Wake of the Dead to War Resistance

"When you realize how many civilians have been killed in the Ukraine War and how many minutes we have to be silent in order to memorate each life, you can really feel the dimensions of this tragedy," says Prokhor Gusev. The Russian exile artist is now working in Northern Norway on his anti-war projects.

Prokhor Gusev gesticulates eagerly. It functions as a sort of warm-up to the show that he will soon be performing at tonight's home theater in Kirkenes, the Norwegian town at the border with Russia. During Pikene på Broen's festival, Barents Spektakel, Gusev is one of 30 independent Russian artists who contribute to the program.

The eager hands express both artistic energy and emphasize war resistance, contemplation, and worry about the future. Recently, Russia's warfare against Ukraine turned one year, and Guvev finds himself in limbo.

"I feel as if February of 2022 will last until the war is over. There can be no real future or new years as long as the war is ongoing," he says.

This fall, Gusev left his home country with his wife. They are both actors and theater directors. After a stay in Kazakhstan, their exile journey went to Tromsø and residence at the Davvi Center for Performing Arts.

Gusev's journey even further north to the border town's Spektakel goes through the Theatre of Resistance – a Russian theater community spread all over the world but united in the resistance against the insanity of the war. Within this framework, he has come into contact with other Russian exile artists and together they have created new performance art.

But before the 'stage curtain' lifts, Gusev has the time to talk about his other projects.

"The most important thing for me now is to be as open and loud as I can – and thereby speak of the Ukraine War, the domestic political situation in Russia, my migration experience, and contemporary art at the theater stage at this special time."

Turning the silence around

In the anti-war project '1 life – 1 person – 1 minute' (1 жизнь – 1 человек – 1 минута), Gusev puts the spotlight on civilian victims of the Russian aggression in Ukraine.

With him are volunteers at the Sakharov Center in Moscow, which carries on the legacy of the Soviet-Russian physicist and peace prize-winning human rights activist Andrei Sakharov.

"It is based on the concept of one minute of silence to memorate the dead. However, the point is to break the silence because many in Russia are silent about the war in Ukraine. Daily we publish a post on Instagram with recordings of everyday sounds as a reminder that more and more people can no longer hear the sounds of everyday life because they have been killed. We also pass on the number of dead and wounded civilians in the war from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Thousands of men and women, boys and girls.

When the project started on the 20th of April, 2104 civilians were confirmed dead in connection to Russia's full-scale invasion. Now the number has nearly quadrupled.

Over 8100 Ukrainians can no longer hear the sounds of buzzing streets, small-talk on the bus, crashing waves and shrieking seagulls, children laughing at the playground, fingers strumming the keyboard, ladles in the pan – the everyday sounds that Gusev and his team remind us that only the living can enjoy.

"I want to continue this project until the Ukraine War is over. With one minute of silence for each dead person per day, it must now last for over 22 years. When you understand how many have been killed in the war and how many minutes we must be silent in order to memorate each life, you really feel the dimension of this tragedy.

He pauses. We both let it sink deeper in.

Parallel realities

And so the stage is set for the show 80 degrees. The theater is a darkened and cool basement – and we as spectators have taken our shoes off, but kept our winter jackets on.

Gusev arrives through the front door, carrying an empty cat cage. Psss, psss, psss, he coaxes. But there is no cat to be found. It had to stay in the home country.

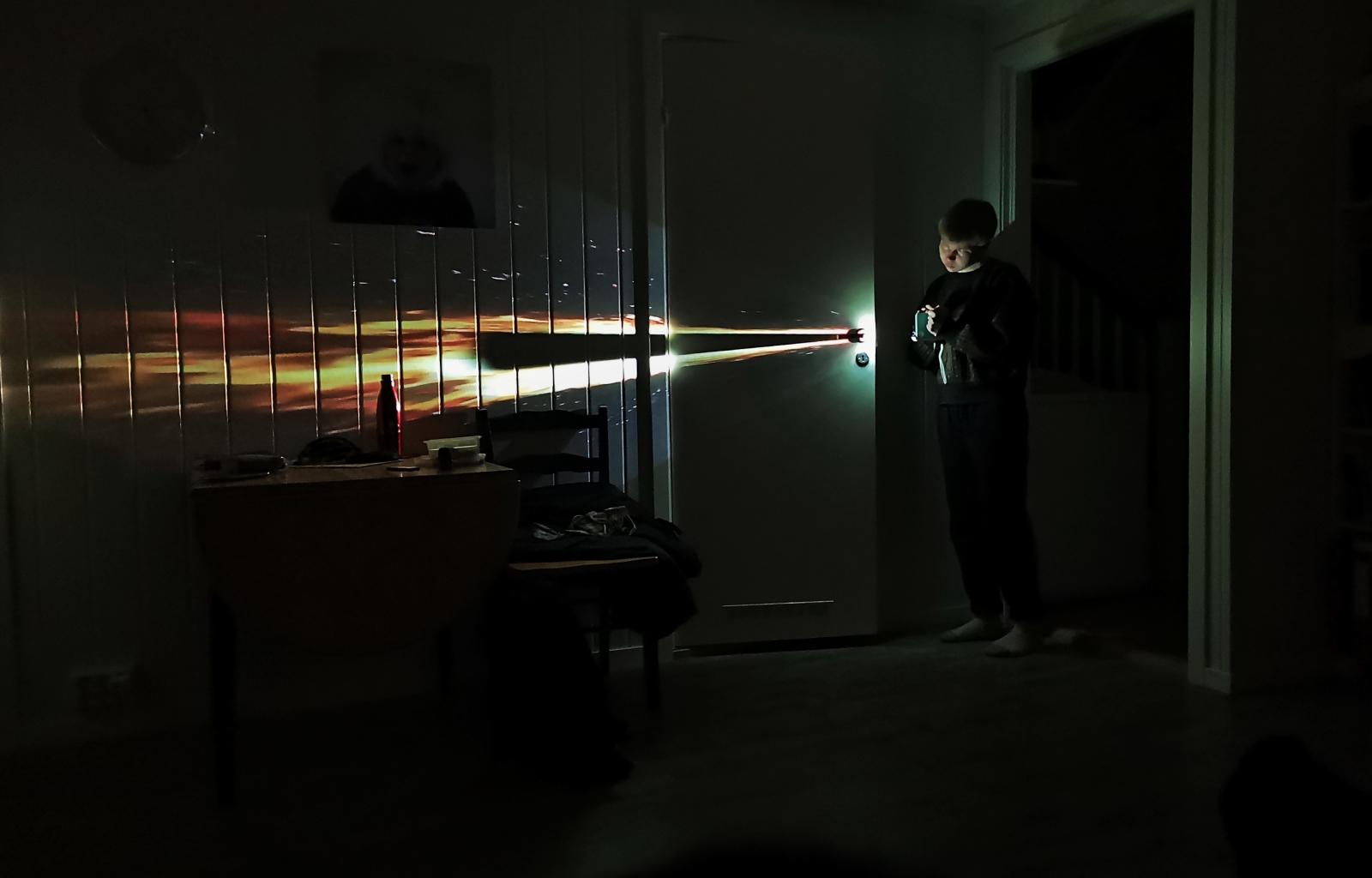

With live images and sound, performed with a small projector and a cellphone, Gusev takes us both further north to icy-cold waters – and east of Russia. We are given insight into the lives of real people.

The Russian marine geologist Alena is on a research voyage in the Polar Sea. Throughout the fall, she exchanges letters in diary formats with the artist Polina in the city of Tula, south of Moscow. The dialogue has been turned into a podcast.

Frostbite, conflict with colleagues, loneliness and yearning, war and mobilization, polar nights, and dark thoughts. This and more can be heard as Gusev projects a whistling wind and a sparkling fire across the living room walls and up toward the ceiling.

From the walls, a pensive animated dog in black and white talks to us. "Some times. Some times I wish I didn't know anything," it says sadly in Russian.

Connected across borders

"With this performance, we try to share the feelings and thoughts of Russian oppositionists – and convey the atmosphere in Russia where one must focus on surviving if one is a war opponent. The performance depicts loneliness at this tragic time but also revolves around the living border-crossing connections between people", says Gusev.

In this case, he is the link between audiences in Kirkenes, Alena in the Polar Sea, and Polina in Tula, who has directed the performance – as well as between the other Russian co-creators in the Theatre of Resistance, who are living in Kazakhstan, South-Africa, and Turkey.

The show was first performed in precisely Tula and will be staged there again this month. And there, as here, the session is rounded off with the audience being invited to write letters to Alena and provide input for the next staging of the play.

"Let us build bridges with paper and pencils and work for peace – which is the most important thing right now," says Gusev.

Gusev illustrates the performance's backdrop by showing photographs of the co-creators and points out on the map where they are located in the world. He also shows photos from the first staging of the play in the city of Tula in Russia.

The long claws of the regime

Problematizing the war and advocating for peace with free speech was not possible in the home country.

At the theater Gusev worked at in Moscow, it was quickly evident that explicit artistic stings against the war would not go under the police's radar.

"We staged an anti-war performance in April and planned more performances throughout spring, but the authorities put a stop to that. The police also canceled other productions because we as producers wore green ribbons, which symbolize war resistance. The censorship became increasingly stricter and criticism increasingly dangerous. We, therefore, had to create more implicit and underground-based communication that the authorities could not as easily understand and catch us for. But we were constantly afraid of the police knowing on our doors and taking us with them", he says.

Since the 24th of February 2022, over 19 500 people have been arrested for anti-war protesting in Russia, according to the human rights organization OVD-info. Fines and up to 15 years in prison is now part of the punishment for spreading "disinformation" about what the Russian military is doing in Ukraine. To date, 477 people are suspected or convicted in anti-war cases.

Lifeline

Gusev and his wife were also particularly vulnerable. He is transgender – and the couple volunteered for OVD-info which provides legal aid for LGBTQ+ persons and political activists.

This fall, Russian legislation targeting sexual minorities and gender minorities was made further stringent. All public expressions of LGBTQ+ are in practice prohibited and may be punished with heavy fines. Since such legislation was introduced in 2013, harassment and violence against this milieu have also increased significantly.

"After the outbreak of the war, we discussed leaving the country. But with low salaries that only cover the cost of housing and food, we simply did not have the economy to go on our own accord. We started sending out our resumès in order to receive residencies or work in other countries. In the end of November, we got an offer from Davvi – and this was our rescue."

(Photo: Sandro Arabyan/Pikene på Broen)

Still on shaky ground

However, this lifeline is now at stake as Gusev's wife risks losing her residence permit.

"A misunderstanding arose at the Norwegian border. She also has a residency at Davvi and had her invitation from the center, but the border guard decided it was a job contract. Furthermore, a case was opened to withdraw her Schengen visa, which is now being processed at the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration, he says and continues:

"For her and for us, losing her residence permit and going back to Russia would be extremely dangerous. In light of my transgender identity and our activism, a return could be synonymous with death."

Although the couple is very pleased with their new residence in Tromsø, this uncertainty about the future is gnawing away at them. The same can be said of the home country's warfare.

"The city reminds me of Coca Cola Christmas commercial with all the lights, the snow and the calm, and the small, cozy houses. But I do not feel calm and safe because of the uncertainty we face and the circumstances in the world. War is ongoing. People are dying."

"I also worry about my parents in Russia because my words here may become dangerous to them. The only thing I know for sure is that I must create art every day."

Migration experiences

In Tromsø, Gusev continues to address topics that arise from the Ukraine War and the political situation in the home country.

"At Davvi, I am now collaborating with other stage performers on the performance Corridor. It is about war, relations between people, and their attempts to live everyday life under these circumstances. After this production, I am planning an interactive show about migration and the feeling of home", he says.

Last fall, as Gusev became one of the hundreds of thousands of Russians who have left their home country following the war, he began creating a podcast about emigration.

"The podcast is called 'Privjet emigrantam' – 'Hi emigrants'. In this, I tell the stories of Russian emigrants of the last century – who left Russia during the revolution and war. I read their diaries and reflect on their experiences and feelings compared to the emigrants of today."

He also describes the podcast as a protest against the Russian regime and against aggression, reign of fear, and discrimination due to ethnicity, national origin, skin color, philosophy of life, sexual orientation, and more.

"The listeners report back that the podcast also makes them feel connected to other emigrants and that they feel less alone in their challenges."

This article was originally published in Norwegian and has been translated by Birgitte Annie Molid Martinussen.