IMO Updates Guidelines on Noise Pollution, But no Mandatory Rules for the Arctic

National Geographic Explorer cruise ship in the Arctic. (Megan Coughlin / CC BY-ND 2.0)

The International Maritime Organization took incremental steps to protecting marine environments, including in the Arctic, from noise pollution. The voluntary measures, however, do not go far enough, say environmental groups and the Inuit Circumpolar Council, especially for the Arctic Ocean’s sensitive ecosystem.

A subcommittee of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) revised the body’s 2014 underwater noise guidelines in an effort to reduce the impact of noise on the marine ecosystem. The IMO previously implemented measures concerning the use of heavy fuel oil and the emissions of black carbon in the Arctic.

While international environmental groups, including the Clean Arctic Alliance and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) welcomed the progress the IMO made on the issue of underwater noise from ships, they urged that quicker and mandatory regulations would be needed, including in the Arctic. The Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) also called for a comprehensive implementation of a noise reduction plan and specific vessel reduction targets.

The Subcommittee on ship Design and Construction revised its 2014 recommendations, but shied away from turning these voluntary guidelines into mandatory regulation. Since the IMO’s guidelines remain recommendatory in nature, only few vessels have implemented them.

Marine mammals rely on underwater sounds to navigate, to track down food sources, and to locate mating partners. Underwater noise pollution disrupts these natural patterns. Large mammals, like narwhals and belugas, are especially sensitive to anthropogenic noise.

Especially harmful in Arctic

“The Arctic Ocean is the last ocean on earth to remain relatively unpolluted by underwater noise, yet the region is experiencing immense pressure from climate change and increased industrial development,” says Melanie Lancaster, Senior specialist, Arctic species, WWF Arctic Programme.

The harm arising from noise pollution is especially high in the Arctic as melting sea and rapidly increasing economic activity, such as shipping, coincide. The melting of sea ice has multiple negative effects. Not only did sea ice in the past limit the amount of shipping traffic in the Arctic Ocean, it also functioned as a “sound buffer” reducing the impact of noise.

We are disappointed

Similar concerns were voiced by the Clean Arctic Alliance.

“While [we] welcome the revision of the 2014 underwater noise guidelines as a milestone in its efforts to reduce the impact from underwater noise from ships on marine wildlife, we are disappointed that the IMO failed to find time to discuss a program of action or to identify the next steps that must be taken”, said Dr Sian Prior, Clean Arctic Alliance Lead Advisor.

Doubled in six years

In the past the Arctic Ocean has been largely free of man-made sounds; bar a limited number of research icebreakers and submarines. However, this is rapidly changing with noise pollution in the region doubling between 2013-2019. And since then traffic volume and maritime economic activity in the Arctic has further increased.

With noise pollution doubling in just six years, action to protect the marine environment in the Arctic is urgently needed, explains the ICC:

“This is significant considering that it took decades for other parts of the world to experience those types of increases.”

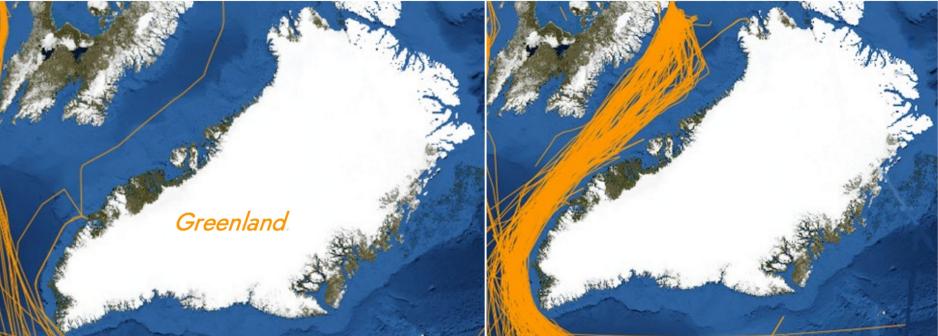

Traffic on the west coast of Greenland 2013 vs 2019. (Source: PAME)

According to the Arctic Council’s working group for the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME), the amount of traffic in the Arctic as measured by distance traveled, increased by 75 percent between 2013 - 2019. Areas that did not see any or only very limited traffic, e.g. the channel between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland saw a substantial increase in traffic from bulk carriers transporting iron from the Mary River mine.

Including Indigenous Knowledge

Environmental groups and the ICC also noted the IMO’s recognition of the importance of Indigenous Knowledge to understanding and addressing the impact of underwater noise.

“What we have seen from Indigenous Knowledge and academic research is that noise pollution from ships has a unique and significant impact in our Arctic marine waters. Noise travels longer distances in cold water and most marine mammals are not used to it. That means there are disproportionate impacts compared to other regions,” said ICC Vice Chair Lisa Koperqualuk.

The voluntary nature of the guidelines is a key issue to further protecting the Arctic Ocean from noise pollution. “There is very little uptake by shipping owners and operators and noise levels are increasing,” Vice Chair Koperqualuk pointed out.

Both environmental groups and the ICC urge the IMO to develop mandatory measures and develop targets and noise reduction plans for specific parts of the Arctic Ocean.

The ICC also calls for the inclusion of an “Arctic Annex” in the IMO guidelines as a concrete way to include Indigenous Knowledge in the policy making process of the IMO.

While the issue of noise pollution is not unique to the Arctic, but occurs universally across the global oceans, the Polar region’s unique environment will require special protections, explains Sarah Bobbe, Arctic Program Manager, at Ocean Conservancy.

“The IMO’s future work on underwater noise must include compulsory measures such as the adoption of limits on underwater radiated noise from ships, so that the overall failure to reduce underwater noise is addressed globally,” concludes Bobbe. “In addition to global measures, even more stringent regional measures to reduce acoustic pollution from vessels in areas such as the Arctic will be necessary.”