Op-ed: Knowledge Needs for Navigating the Central Arctic Ocean

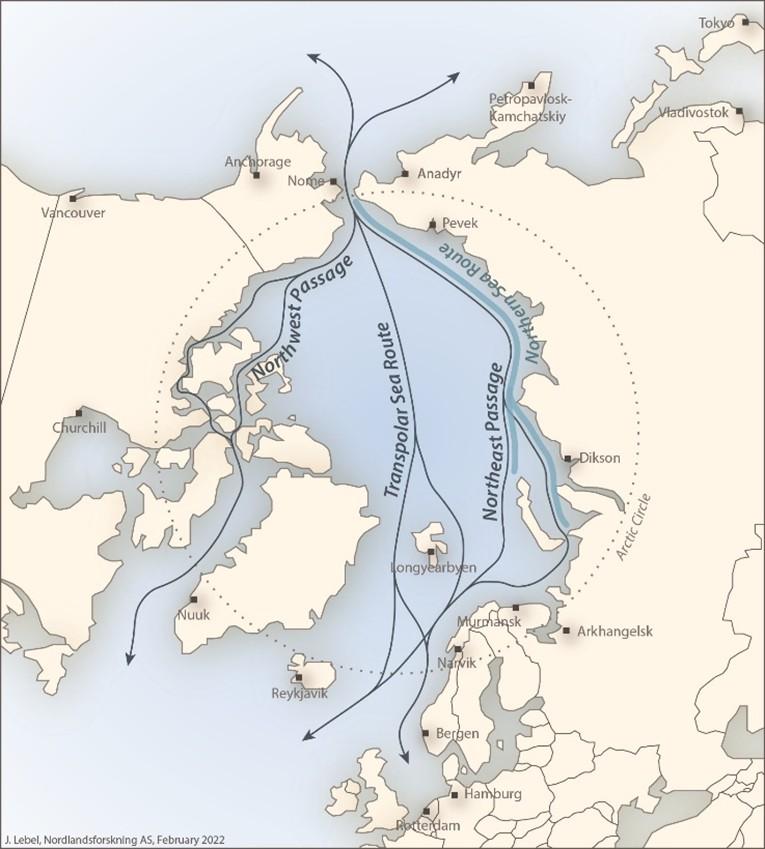

The Central Arctic Ocean is becoming more accessible for shipping. (Source: Julien Lebel)

Op-ed: The Central Arctic Ocean is becoming more accessible for shipping. The ability to navigate at the top of the globe presents new opportunities, risks, and uncertainties. We need more transdisciplinary research to develop proactive responses to shipping growth, writes Julia Olsen, Associate Professor at Nord University.

This is an op-ed written by an external contributor. All views expressed are the author's own.

Existing Arctic shipping routes

For centuries, ships have operated in Arctic waters, primarily along the sea ice edge. Famous explorers long sought shorter routes between Europe and Asia. Then, ships began transiting the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage in the early 20th century.

Today, Arctic waters—especially the Barents Sea, the Bering Strait, and the Russian Arctic waters—are actively utilized for commercial shipping. Vessels in this region engage in activities like fishing, marine tourism, petroleum and mineral resource extraction, and research. According to the Arctic Council, vessel operations in Arctic waters have increased by 37% between 2013 and 2024.

A recent analysis indicates that transit cargo along the Northern Sea Route reached a new record in 2024: 97 voyages and 3.1 million tons of transported cargo.

Opening of the Transpolar Sea Route

Until recently, navigation in the Central Arctic Ocean (CAO), which is predominantly a high seas area surrounding the North Pole, received little attention. The CAO covers an area of 2.8 million square kilometers, which is slightly larger than the Mediterranean Sea.

An expedition cruise vessel will begin a journey from Svalbard to Alaska via the geographic and magnetic North Poles.

The shortest Arctic route, the Transpolar Sea Route, crosses the CAO. It allows vessels to bypass the jurisdictions and regulations of Arctic coastal states. This route is approximately 13–17 days shorter than those that pass through the Suez Canal.

Despite these advantages, the Transpolar Sea Route is often described as a hypothetical route due to the persistence of sea ice, which currently makes navigation impossible for non–ice class vessels.

Icebreaking vessels have been navigating the CAO for several decades. The Russian icebreaker Arktika reached the North Pole in 1977. Since the 1990s, other Russian icebreakers have made multiple tourism trips to the North Pole. Research icebreaker vessels from various countries operate in the CAO. For example, the year-long MOSAiC research expedition used the German research icebreaker Polarstern in drifting sea ice near the North Pole in 2019–2020.

New chapter

The French operator Ponant recently opened a new chapter in the history of commercial shipping. The company built a Polar Class 2 cruise vessel, Le Commandant Charcot, which is suitable for operating in and transiting through the CAO. In 2021, it sailed to the North Pole.

Now, in just a few days, this expedition cruise vessel will begin a journey from Svalbard to Alaska via the geographic and magnetic North Poles.

The disappearance of sea ice, technological advances in the shipping industry, and increasing interest in the Arctic and its resources will likely lead to shipping expanding into new areas. The climate models project that the CAO is expected to become more accessible for navigation in the next 20–25 years.

Is it only a matter of time before the Transpolar Sea Route is incorporated into the global maritime network as a route for transporting cargo between Europe and Asia?

Uncertainties and opportunities

There are many uncertainties associated with navigating in the CAO or along the Transpolar Sea Route.

The remote location and long distances from ports and search-and-rescue services increase the operational risks. Additionally, environmental issues in the CAO could affect other seas and coastal areas that are an integral part of Arctic communities’ livelihoods.

Only a matter of time before the Transpolar Sea Route is incorporated into the global maritime network between Europe and Asia?

Shipping might result in oil spills, water pollution, or emissions in the seas and coastal areas that vessels pass through. Little is known about the consequences of icebreaking and shipping pollution on sea ice, which is a vital place for marine species and a regulator of climate systems.

Despite the uncertainties and risks, the opening of the CAO presents new opportunities for shipping operators. Cruise companies can offer passengers the unique experience of visiting one of the most-remote places on Earth. Research expeditions can collect new data to better understand climate processes.

Additionally, several fishing vessels have responded to fish species’ northward migration by beginning to operate on the outskirts of the CAO. However, fish and other marine species might not be able to migrate farther north due to the scarcity of nutrients there.

Moreover, the CAO Fisheries Agreement currently bans commercial fishing until 2037.

The opening of the CAO presents new opportunities for shipping operators.

More knowledge for proactive responses

Numerous international, pan-Arctic, and national regulations exist to mitigate maritime operations’ negative impacts. However, few of them apply to high seas and ice-covered waters.

The fast-approaching opening of the CAO necessitates additional proactive responses. Consequently, there is a need for transdisciplinary research on the route’s economic feasibility, as well as the social and environmental impacts of shipping operations.

Such research should involve multiple relevant stakeholders, even if they hold differing views on the future of the CAO. These views may range from advocating for or opposing new shipping regulations to supporting the complete protection of sea ice and the Arctic wilderness.

Compared to shipping in other places, shipping development in the CAO is still in its infancy. Maybe now is the time to ensure it matures in a sustainable way, by generating more relevant knowledge and stakeholders’ voices.

As a recent Arctic Council report concludes, “it would be wise to develop a proactive approach and have international regulatory frameworks ready before these activities commence.”