Spitsbergen or Svalbard? The Answer Includes both Politics and History

Perhaps this was the first thing Willem Barentsz saw when sailing to Svalbard in June 1596? The rugged peaks on the northwestern side of the archipelago are the source of the name ‘Spitsbergen’. Photo: Rita Willaert

Before the Svalbard archipelago became Norwegian in 1925, the area was called Spitsbergen. It is still important to Russia to refer to the islands with their historic name, though a number of other countries also do. We explain the many terms and conflicts related to the 100-year old Svalbard Treaty.

Russian authorities used the 100th anniversary for the signing of the Svalbard Treaty from 1920 to vocally attack Norway on how Norway manages the principle of equal treatment of signatory states on the archipelago.

In a letter from Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov to his Norwegian counterpart Ine Eriksen Søreide, he consequently refers to the archipelago as ‘Spitsbergen’ or ‘the archipelago’.

And not just that. In a written comment to the Norwegian economy web site E24, the Russian embassy explicitly asks that the area be referred to as ‘Spitsbergen’ in print.

“This is not just a name, it is also politics”, says Jørgen Holten Jørgensen. He currently works as Head of Administration at Berlevåg municipality in Troms and Finnmark, however, he is a former researcher and diplomat.

He has also published the book ‘Russisk svalbardpolitikk: Svalbard sett fra den andre siden’ [Russian Svalbard policy: Svalbard as seen from the other side].

“The Russians’ referring to the archipelago as Spitsbergen has a political reason, though Spitsbergen was also the historic name from before 1925. Norway chose to name the archipelago Svalbard, and then referred to 14th century sagas about ‘Svalbard has been found’. There are probably no evidence of this, and what might potentially have been found was the ice edge. Nansen was one of those who actively used this to refer to Norwegian historical link to this area”, Jørgensen says.

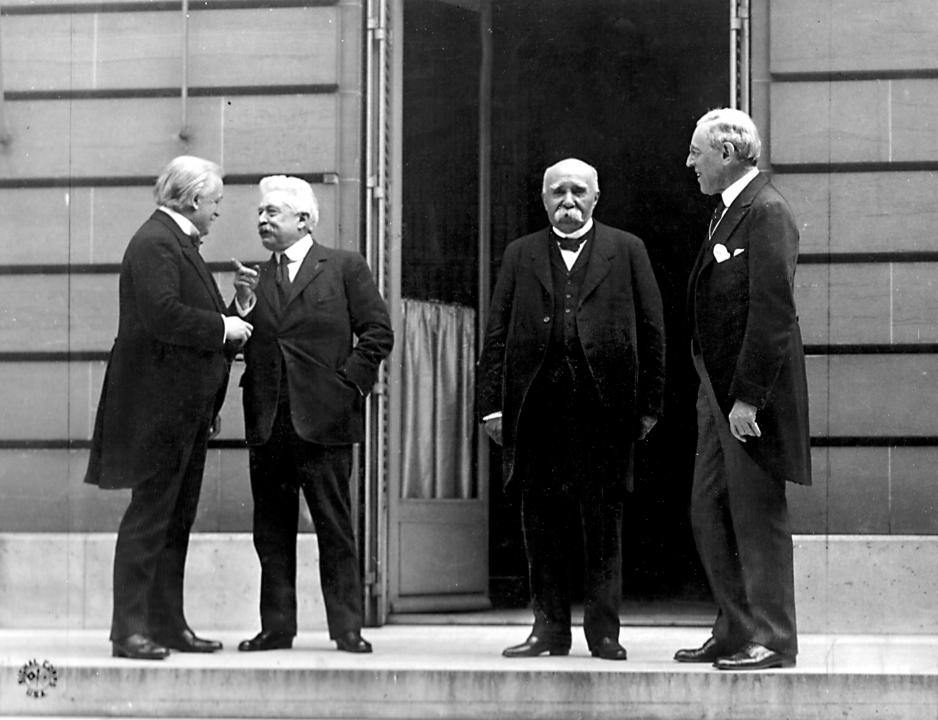

“The Four Big” gathered during the Paris peace conference in 1919; David Lloyd George from Great Britain, Vittorio Orlando from Italy, Georges Clemenceau from France and Woodrow Wilson from the USA. These negotiations led to Norway’s being granted sovereignty over Spitsbergen, which was later renamed Svalbard in Norwegian. Photo: Wikipedia

Not invited to the Paris talks

Spitsbergen was the name of the area over which Norway was granted sovereignty during the peace negotiations following WW1. The new Soviet state was not invited to the 1920 Paris meeting, and even though the new Moscow government later both acknowledged Norwegian sovereignty over the archipelago and signed the treaty, the name Svalbard will never be used by Russian officials.

“When Norway assumed sovereignty over Svalbard, Spitsbergen was renamed Svalbard. That was to symbolize that we reclaimed an area that had belonged to Norway before. Even back then, Russians voiced their historic considerations about how Russian trappers had sailed to Svalbard long before the 1400s. By changing its name, Norway naturalized the narrative that we were here first”, says Tora Hultgreen, head of Svalbard Museum. She wrote her PhD about Russian trappers on Svalbard.

100 years after its being signed, the Svalbard Treaty is once again at the forefront of Norwegian minds. High North News has attempted to clear up the concepts used when talking about Svalbard and have therefore asked some of the best experts in the field for help.

Where does the name Spitsbergen come from?

When Norway was awarded sovereignty over the archipelago during the peace negotiations following WW1, the area was called Spitsbergen. The name comes from the man who discovered the archipelago towards the late 1500s, the Dutch explorer and sailor Willem Barentsz.

West Spitsbergen was the original name of Svalbard’s biggest island, and the word literally means ‘rugged mountain peaks’. The island is today called Spitsbergen and that is the island on which both Longyearbyen and the Russian settlement Barentsburg are located. That also goes to explain why Norwegian meteorologists refer to ‘Spitsbergen’ when forecasting the Svalbard weather.

Who came to Svalbard first?

From the late 1970s, Soviet archeologists started excavating several of the old Russian trapper stations on Svalbard. Their goal was to find evidence that Russian trappers and hunters first discovered Svalbard in the early 1500s.

“One argued that evidence was found for the oldest stations stemming from the early 1500s through dating drift wood used to build them. However, this does not provide reliable dating of when the building was used, as there has always been driftwood up here, says Tora Hultgreen at Svalbard Museum.

There are evidence that the aforementioned Willem Barentsz came to the archipelago in June 1596.

“His diary notes say that he has arrived in a place where no man has ever been before. That was very genuine. The year before, Barentsz had conducted an expedition to Novaya Zemlya. In the diaries from there, there are descriptions of traces from Russian trappers, remains of foundations from houses and big Orthodox crosses. Barentsz mapped the western coast of Svalbard. If there had beent races of Russian trappers, this would have been noted in his diaries, says Hultgreen.

Is Russia the only country to refer to the archipelago as ‘Spitsbergen’?

No. The Netherlands also use Spitsbergen. English literature mentions Spitsbergen. However, in Russian literature, the archipelago is referred to as Grumant, which is a russified version of the term for Greenland. In earlier times, one did not know whether these islands were part of Greenland or not, as there was much ice in the area.

One heard about the island, long before it was possible to start trapping here, from Dutch sailors arriving to Arkhangelsk on their merchant ships. Therefore, the first Russian coalmining town on Svalbard was called Grumant.

There are no indications that Russian Pomors came here before some time between 1704 and 1710. Here, Lenin is guarding the Russian settlement in Barentsburg. Photo: kudinov_dm

When did the first Russians arrive at Svalbard?

There are no indications that Russian pomors came to Svalbard before some time between 1704 and 1710. They started trapping on Svalbard following a direct order from Czar Peter the Great. He also wanted to be part of the lucrative whaling industry.

“However, the Russian did not master the technique, nor was there much whale in the sea due to a large outtake in previous years. Thus, the Russians started hunting game and also started wintering. It was actually Russian pomors who taught Norwegians how to winter at Svalbard”, says Hultgreen.

What is the Fisheries Protection Zone?

The Fisheries Protection Zone stretches out 200 nautical miles around Svalbard and was introduced in July 1977. Fishing is not banned inside this zone, despite what its name may indicate; however, the access to fishing in this area is established based on traditional fisheries in the area.

The areas around Svalbard are good for fishing and fish abounds. However, the Soviet Union – and later Russia – has always protested against Norway’s one-sidedly introducing this Fisheries Protection Zone, where Norway exercises jurisdiction and controls fishing vessels.

Fisheries in the Fisheries Protection Zone is part of the overall fisheries management of the Barents Sea, about which Norway and Russia cooperate. Thus, no separate quotas are licensed for fishing in the zone. Russian vessels are the most active in the area, explains researcher Arild Moe at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute.

“Russian vessels do not appreciate being arrested by the Norwegian Coast Guard if they fish with illegal methods or take up protected fish species. Therefore, the Russians take a series of formal measures to mark their displeasure, for instance not signing inspection protocols. This is the principal attitude. However, Russia also benefits greatly from the Fisheries Protection Zone. Because it makes sure that vessels from third countries that were not fishing in the area prior to 1977 can be excluded and could be controlled if they were to get quotas from Norway or Russia. If the principal Russian view were to be executed, that would affect Russian fisheries”, Moe says.

The creation of the Zone was controversial at the time, and it still is, Jørgen Holten Jørgensen explains.

“Norway reserves the right to create an ordinary economic zone around Svalbard, but out of fear of international opposition it was rather chosen to reduce the significance of the Zone somewhat – and thus it was referred to as a Fisheries Protection Zone”, Jørgensen says.

The Coast Guard vessel KV Svalbard conducting a fisheries inspection onboard the Russian fish processing vessel Arctic Princess in the Recherche Fjord off the coast of Svalbard in 2014. Photo: Torbjørn Kjosvold

Why does Russia object to the expansion of the protected areas on Svalbard?

Moscow considers Norway’s introduction and expansion of protected nature areas on the archipelago as a threat to Russian business activity. This applies in particular to mining, but there is also fear that the so far limited Russian tourism in the old mining communities will be threatened by an expansion of the Norwegian protection regulations.

Russia has also objected against restrictions on the use of helicopter. Today, helicopters are only permitted for transporting crew and workers to and from Barentsburg from Svalbard Airport.

One has to apply for permission each time for any other flights. Russia has always argued, in general, that the Norwegian protection regulations are so strict that they are in violation of the Treaty’s basic rules about the right to mining.

“This is also an old issue. The nature protection regulations and protected areas on Svalbard are extensive. Some years ago, Russia argued that their plans about a new mine in Coles Bay, not too far away from Barentsburg, were thwarted by Norwegian protection authorities, as the Russians wanted to construct a road there. One wanted to demonstrate that potential development plans for mines would not be hampered by nature protection regulations. From the Norwegian side, it was emphasized that the Treaty only gives the right to mining insofar it follows local laws and regulations. Besides, the Treaty places a particular responsibility on Norway for preserving nature. In reality, establishing new mines would probably not be viable for Russia due to economic reasons.”

“In reality, thus, the conflict over protection policies has not been that intense. However, another industry is emerging now – tourism. And tourist traffic does not only happen with helicopter, it also happens with vessels. There is tension between nature protection considerations and economic considerations”, says Arild Moe at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute.

Is there still a perception in Russia that they were the first to discover Svalbard?

“If you visit the museum in Barentsburg, this view is very evident. It is very important there to communicate that “we were here first”. The issue is probably not that important in Moscow today, though it is brought into the limelight at regular intervals. The historic tradition varies between the two countries, without this currently being an important archeological issue in Russia. It was more important during the Soviet era”, explains Tora Hultgreen at the Svalbard Mueseum.

When did Russian mining on Svalbard commence?

The first Russian prospecting of coalmining on Svalbard happened in 1912, in Grumant. Operations were not fully up and running until the late 1930s. in 1932, the Soviet Union bought Barentsburg from the Netherlands. That is why this one settlement is called Barentsburg and does not have a Russian name. The coal deposits in Pyramiden were acquired from Sweden. Mining here was not fully operational until after WW2.

Russians first heard about Svalbard from Dutch merchants sailing to Archangelsk. Back then, it was generally believed that the island was linked to Greenland. Thus, the archipelago was referred to as Grumant in Russian for a long time; a russified version of the Dutch word for Greenland. Pictured above, the first Russian settlement of Grumant. Photo: Sigurd Rage

This article was originally published in Norwegian and has been translated by HNN's Elisabeth Bergquist