Container Shipping Is Coming to the Arctic along Russia’s Northern Sea Route

Signing of the container shipping agreement during the International Arctic Forum in April in Saint Petersburg. (Source: Courtesy of Primorsky CPC)

Plans to build container shipping terminals along Russia’s Northern Sea Route continue to move forward. While experts remain skeptical about the project’s feasibility, the lead company, Primorsky CPC, announced the construction of a new port near Murmansk.

The transport of natural gas and oil along the Northern Sea Route (NSR) has seen rapid growth with cargo volume quadrupling between 2015-2018 to nearly 20 million tons. Now a Russian company, Primorsky CPC, aims to bring container shipping to the route and take advantage of the shorter distance between Europe and Asia. Similar to Novatek’s approach of building transshipment hubs on the Kamchatka and Kola Peninsulas, Primorsky announced plans for large container terminals along the eastern and western terminus of the NSR.

The Kamchatka Development Corporation (KRKK) and Primorsky Universal Handling Company (Primorsky CPC) signed an initial agreement during the International Arctic Forum in April in Saint Petersburg on April 9th. The accord envisions the construction of a container terminal near Leningrad and another on the Kamchatka Peninsula, to be completed by 2022 and 2024 respectively.

Primorsky CPC now revealed further details explaining that it will also build a container terminal on the Kola Peninsula. “The terminal near Murmansk will become the western anchor point of the Arctic part of the Asian-European container line, which we are starting to build. You already know the Eastern terminus is in Kamchatka,” Primorsky CPC’s director Andrei Sizov, explained. The plan is for the Murmansk and Kamchatka hubs to collect cargo arriving from Asia and Europe before transshipping it on ice-class container ships along the NSR.

Can container shipping work?

The idea to create a “container shuttle” on the route is not new and by using ice-class container vessels the shipping season can be extended, explains Arild Moe, Senior Research Fellow at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute. “It might be that some cargoes can be reloaded and collected in either end and sent with such a ship. However this set-up obviously will involve some extra time used and also reloading costs.”

The reloading of cargo at both the Eastern and Western terminus will add several days to the length of a voyage and adds substantial costs, reducing the two primary incentives of shipping via the NSR. “The idea of Arctic transit shipping is that it is faster and cheaper. If there are two transshipments; if we add the surcharge for the regular carrier to make a rerouting to these transshipment ports; if we add the purchase and operation cost of the Arc7 carriers, then will the transit cost still be very attractive,” explains Frederic Lasserre Professor at the Université Laval Québec.

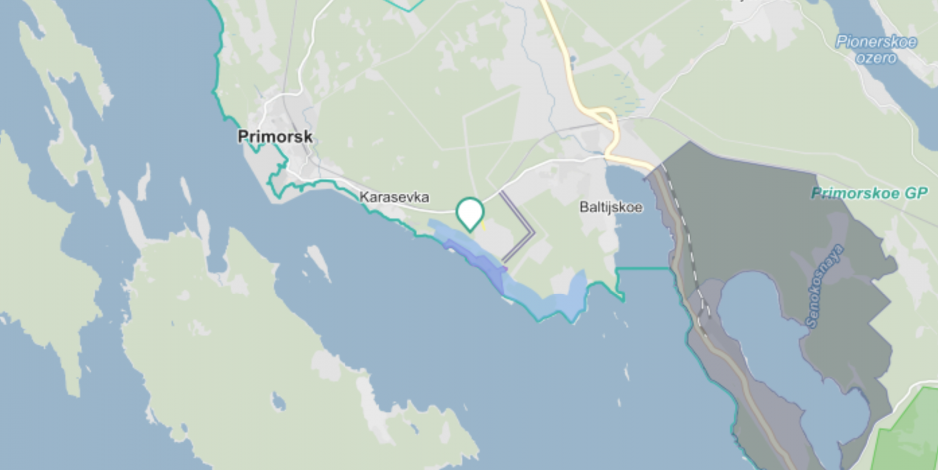

Map showing the approximate proposed route and location of the transshipment hubs. (Source: Author’s own work)

Experts remain skeptical

Experts question the economic feasibility of container shipping along the NSR. The route has so far only seen a single container ship when Danish shipping company Maersk sent the first-ever container ship along the Route from Far East Russia to Germany in September 2018.

There are a number of challenges with shipping containers via the NSR, says Frédéric Lasserre Professor at the Université Laval Québec. It may be difficult for Primorsky CPC to find sufficient customers as container shipping companies would have to reroute either ships or containers to remote ports in Kamchatka and Murmansk, which may constitute 4-5 day detours from main shipping routes.

Delays due to ice conditions also represent a potentially costly challenge as customers frequently rely on on-time deliveries. Furthermore, usually schedules are the same year-round. Shipping through the NSR would require summer and winter schedules, which may be hard to make work with existing logistics networks.

Industry insiders also caution that the project looks more like a PR stunt than a serious investment project. “The project is not realistic. There is no fleet of ice-class container ships and it can not be developed by 2024,” explains Alexei Bezborodov of transport research agency InfraNews.

Nonetheless, while financial and planning details remain vague, Primorsky CPC does have a track record of constructing a major port development in the Leningrad region handling up to 70 million tons of cargo per year.

Selecting terminal locations

The Murmansk and Kamchatka terminals will be designed to handle up to five million TEU (containers) per year once fully completed, with an initial capacity of 3 million TEU. From the hubs cargo will be distributed onwards to ports in Europe and the port of Primorsk near Leningrad. Sizov foresees about 60 percent of cargo heading towards European ports and 40 percent going towards Primorsk. In comparison total container shipping volume between Europe and Asia currently stands at 22 million TEU.

The Primorsk port will be located 1.5 kilometers from the existing Primorsk facilities and six kilometers from the Yermilovo Railway Station. The location features a natural water depth of 18 meters allowing for virtually all types of vessels to call at the port without the need for dredging.

Construction plans for the Construction "Primorsk seaside universal transshipping complex". (Source: Courtesy of Leningrad Region Administration)

Primorsky CPC is currently evaluating different locations for the NSR container terminals. In Kamchatka three potential sites are being evaluated and construction will begin within two years and all three phases of the project, including the container terminal, the port infrastructure, and the connection to land-based infrastructure, will be completed by 2035, explains company’s director Andrei Sizov.

On the Kola Peninsula the potential locations are Ura-Guba along the Barents Sea about 50 km from the Norwegian-Russian border, (the Barents Sea coast, 9 km west of the Kola Bay), the Kildin Strait to the northeast of Murmansk, and Kildinsky Strait (separates Kildin Island from the Murmansk coast of the Kola Peninsula) and the Teriberskaya Bay a bit further to the east.

The entire project is estimated to cost $4.1bn, with the Kamchatka terminal coming in at $900m. The company plans to finance the development without government support by attracting private sector investments.

“This is not just an ordinary agreement: this is the creation of a ‘gateway’ for entry and exit to the national Arctic transport lines,” said Nikolai Pegin, head of the Kamchatka Development Corporation. “And this line will link whole continents.”

Ice-class container ships

The company plans to build a fleet of Arc7 ice-class container ships by 2024, similar to Novatek’s fleet of LNG carriers. The vessels will be designed to operate on LNG, reducing harmful emissions. Only 8-10 such vessels would be required to maintain a weekly and year-round schedule along the route and the results of preliminary design studies are expected by September 2019, Sizov explains.

“Ice-class vessels are the best to ply the NSR, in open waters they are clumsy and uneconomical to run. It makes more sense to have them offload [their cargo] at transhipment terminals,“ confirms Prof. Lasserre from Canada.

Year-round navigation on the NSR will be possible by 2030 due to ice loss and with the support of the Leader-class 120MW icebreakers, the company explains.

However, with rapidly growing levels of traffic, icebreaker availability especially along the eastern reaches of the route will be questionable. Also, the Kamchatka hub may require standby icebreaker services during winter to keep the port ice free, adding additional costs, Lasserre cautions.

Comparisons to Novatek

Primorsky CPC highlights the commonalities with Novatek’s recent projects, including the goal to use transshipment hubs to limit the distance that ice-class vessels need to travel. In fact, many experts were equally critical about Novatek’s plans highlighting the area’s remoteness, rising construction costs, adverse climatic conditions, and limited transportation options, as obstacles to success.

Just ten years ago there were no Arc7 ice-class LNG carriers and no LNG plants above the Arctic Circle. Now, a dozen LNG carriers conduct a regular year-round shuttle service to export products from Yamal LNG to Europe and Asia, Primorsky CPC points out.

Nonetheless, the NSR may not yet be ready for container shipping. Andrei Karpov, Director at the Saint Petersburg-based analytical firm Dorn explains that in the short to medium-term the NSR will not conquer a large share of the container shipping market. However, possibilities may change after 2030 as ice continues to decline and if new icebreakers become available.

It is also important to not overstate the potential of Arctic shipping, Moe from the Fridtjof Nansen Institute cautions. “There can be models that work for some niches in the market - perhaps refrigerated fish – without changing trade volumes on a global scale.”

Prof. Lasserre concludes with a similar analysis. “It may prove successful in tapping into a niche market, e.g. containers from northern China to northern Europe.”

While traditional logistics models may today not see much potential for container shipping in the Arctic, given the region’s rapid climatic change, it wouldn’t be the first time that economic calculations have to be adjusted in the High North.

Arild Moe and Frédéric Lasserre. (Source: Courtesy of Moe and Lasserre)