In Svalbard, Russians and Ukrainians Live Side by Side

Longread: “When the people who are fighting are those you have had beer with, sat face to face with time and again, it hits you in a different way”, says Russian Sergey Chernikov.

Julia Litvinova is facing a short wall showing video clips from the war in her home country Ukraine. Around her neck, a comforting arm. In 2014, she got on the final train out from Luhansk when armed fighting erupted there. We will return to her story later on. First, there is the opening of an exhibition at Spitsbergen Art Center.

Next to the projector we find Russian Sergey Chernikov, is eyes turned towards bombed-out buildings.

Both he and Julia used to live in the Russian settlement of Barentsburg, just some 40 kilometers in a straight line from Longyearbyen. Now they, and many of their friends, have worked on this exhibition that is to benefit humanitarian assistance in Ukraine.

“All I knos is that we must support each other. Everybody in the whole world. If you give love, you get love. If you sow hatred, you reap hatred”, Sergey says.

Svalbard Art for Peace

Supporting Ukraine

“Not forgotten”

Before the invasion of Ukraine, the Svalbard artists Elizabeth Bourne, Olaf Storø and Stein Henningsen had planned an exhibition at Spitsbergen Art Center in Nybyen, Longyearbyen. At the time, the building had not been used for any activities in quite a while. There was no art on the walls, just yoga mats and a rack with tights and sweaters with a text about remembering to breathe.

When Russia attacked Ukraine, they decided to turn a part of the gallery into a Ukraine room. They asked Sergey and his friends if they wanted to fill it.

Two days before the opening of the exhibition, the smell of wet paint simmered into the shared kitchen at the art center where the undersigned rents an office space. It came from the exhibition rooms inside. Sergey had drawn up a rectangle o the wall. Now, he pulled broad brush strokes along the upper part of the rectangle, painting it blue. On the floor; a box of yellow paint.

“I have friends in Ukraine. Friends I have from Barentsburg have families in Ukraine. Friends’ relatives are there. You can see pictures from a faraway war without its leaving a too heavy impression on you, however, when those who fight are people you have had beer with, sat face to face with repeatedly, it hits you in a different way”, he says.

Living in Barentsburg was nice. Everyone were friends.

“Everybody was friends”

Sergey came from Moscow to Svalbard and the Russian settlement of Barentsburg in 2015. He started working as a guide and later expedition leader in Grumant, the tourism company of the Russan state-owned mining company Trust Arktikugol.

In Barentsburg, Russians and Ukrainians live and work side by side. The tourist industry staff comes from both countries, and many of the miners are from the Donbass area in the eastern part of Ukraine.

“Living in Barentsburg was great. Everybody was friends”, Sergey says.

He starts telling a story he argues illustrates this well: There was a girl who decided to boil borsch soup but found out that all she had was a pot. She asked the other residents of the house, and jusi like that she had all the ingredients she needed.

“That is how it was”, Sergey says.

Last year, he moved to Longyearbyen together with several others from the tourist company.

According to the Svalbard Governor, 120 Russians and 220 Ukrainians live in Barentsburg now.

Heart for Ukraine

Julia Litvinova creates heart-shaped pins that are to be sold off to raise funds for humanitarian assistance to Ukraine.

Sergey has spoken with some former colleagues and believes they are rather stressed, though he points out that he does not have a full overview over the situation.

“In Barentsburg, people are safe from the physical war, however, they are affected by what happens in their home countries. Many have friends and family in Ukraine. They do not know what happens next”, he says, before adding that this is not something that applies just to Barentsburg.

People he has spoken with elsewhere in the world think the same. What will the future hold now?

Sergey was shocked when the world stared. He had not believed there would be armed conflict.

“The only thing we can do now is to stop the war. Children and women are dying. After that, we can discuss the future. What is certain is that Russia and Ukraine never will be the same again”, he says.

Artist Elizabeth Bourne runs Spitsbergen Art Center. (Photo: Line Nagell Ylvisåker)

Tourism boycott

In the years after Sergey’s arriving in Barentsburg, the tourist industry grew fast. In 2014, there was a staff of two in the company. When High North News visited Barentsburg in the fall of 2020, they had a staff of 80 and was continuing building its business, despite the pandemic.

Last week, Svalbard Tourist Council advised all its members to not leave any money in Barentsburg, as the company is operated by the state-owned Trust Arktikugol.

“The background for this is the escalation of the war against Ukraine and all the meaningless things going on there. We want to make a point to the Russian state and its regime”, Chair of Visit Svalbard Ronny Strømnes said to Norwegian broadcaster NRK.

This has stirred debate in Longyearbyen. When the artist Olaf Storø enters the gallery room to finish preparing his part of the exhibition, he has just been interviewed by NRK. They asked him what he thinks about Svalbard Tourist Council’s advising its members not to buy services in Barentsburg. Storø tilts his white-haired-and-bearded face and pulls a lot of energy to utter the words he wants to communicate:

“I am now considering withdrawing from Visit Svalbard. We have always been friends with the people of Barentsburg, despite politics. We do now know what the consequences will e if we ruin this. We do not want any ‘split and divide’. That is why we thought people could come here, to the Ukraine room, and leave a heart around their thoughts”, he says.

I am now considering withdrawing from Visit Svalbard

He himself was looking through his pictures and found a print of a yellow and blue polar bear with the text “keep out”. He will auction it off to raise funds for humanitarian assistance to Ukraine.

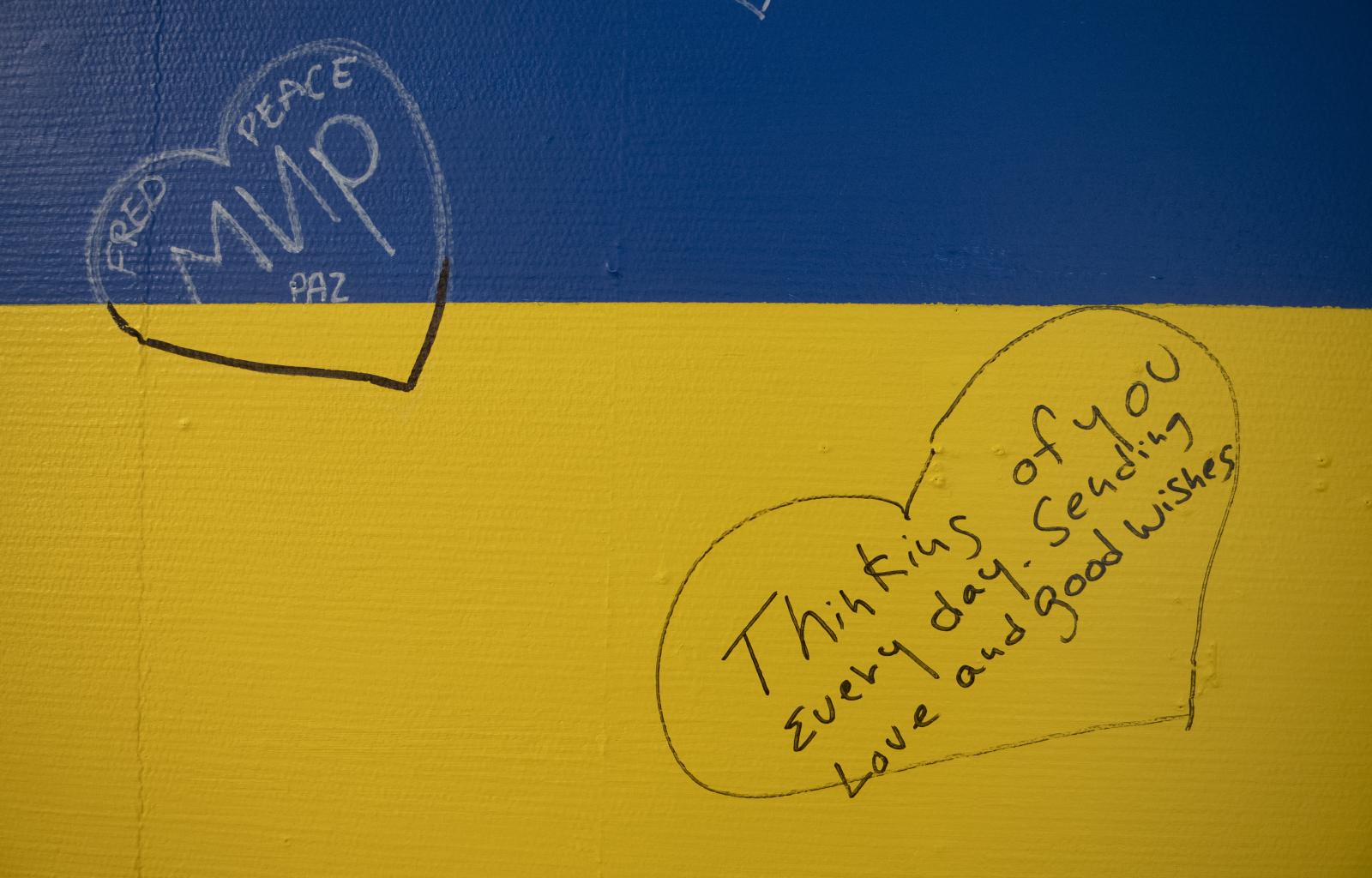

The bear is roaring right in the middle of the Ukraine room. Sergey, Julia and their friends from Ukraine and Russia fill the rest: The large flag onto which people may write messages of support, the text saying ‘We stand with U’ and a photo montage showing the two realities: Pictures from Russia – and from Ukraine.

“I have seen so much horror and am thinking: What can I as one single person do about this?”, Sergey asks before answering himself:

“I feel we should do more, be more aware of human lives, that people are dying. Not just in Russia and Ukraine, but all over the world. All lives matter. However, we can raise funds and create change for some and do our best to stop the war”, he says.

Segey believes it takes a mental change. Psychology is at the core. The most important thing people can do is to contribute to love, to care and support, to not feed negative feelings.

Sergey also believes it is important for people to think themselves. Not just scroll through the days and take in floating bits of information passing by.

“We should not believe everything. Stop, think about what you read, how you read it, analyze it”, he says.

Olaf Storø auctions off the litography called “Keep out”

He initiated a Ukraine room at Spitsbergen Art Center.

Security is most important

Between organizing and doing meticulous work to get her own paintings onto the wall, Elizabeth Bourne says the Svalbard Governor Lars Fause has agreed to open the exhibition. I call him to ask how the war in Ukraine is affecting Svalbard.

Fause stresses that all of Svalbard is Norwegian territory, and that Norwegian law and human rights stand firm here. The Svalbard Governor’s main job is to maintain security in the community, security on and around Svalbard. All the governor’s proxies are still in force.

“We treat everybody on the archipelago the same, be it about rescue, preparedness, public safety, or service. Russian citizens are treated just like everybody else; I can assure you of that”, he says.

The Svalbard Governor adheres to guidance from Oslo and maintains necessary dialogue with the Consulate General in Barentsburg. The Governor will continue having an office day in Barentsburg on the last Friday of the month, as usually. Then, the police shows its presence and the Governor’s office is available to the public in Barentsburg. The regular contact meetings with Trust Arktikugol, the next one scheduled for mid-May, will also be conducted as per usual.

Do you fear tensions between the settlements or within them, I ask.

“What I will say is that we keep our eyes open. In a worst-case scenario, we will put on our police and legal hats. That is no different from how it has been. However, no incidents have been reported to us. I have said ‘keep calm and carry on’”, the Governor says.

I also ask him what normal people should do in this situation.

“What characterizes Norway is that we have the freedom to move about and to speak our mind. That is still the case. I have to admit that many have asked me for advice. I say that the regular freedom of action is there, just as it has been. However, I also have a desire for people to use that freedom and embrace it with a heart. That is a nice frame that is also characteristic of Svalbard. Put a heart around it and you will always be on safe ground”, he says.

The war in Ukraine came as a shock to us, just like it did to everyone else

Sowing hearts

A sowing machine rattles away on the firs floor of the Art Center on the day before the opening of the exhibition. Julia Litvinova is bent over a yellow heart. She is attaching another, smaller blue heart to it. On the back side, she will put a pin. The hearts as well as bracelets she has braided are to be sold off to raise funds for humanitarian work in her home country Ukraine.

Julia comes from a small place at the heart of Donbass, and she studied in Luhansk when armed Russian separatists took control over the area in 2014. She got on the very last train out from the town and the war zone and traveled to friends in Kharkiv. Being a refugee from the war area, she received support from the German Red Cross after visiting a migration office, a welfare office, and filling out a series of forms.

Friends got her a place to live. Her money went to food and clothes. She was only going to go away for a couple of weeks, however, when fall came, she realized that the situation would not change. Julia got a job as a tailor in Ukraine and sowed everything from wedding dresses to gymnastics’ clothes.

In Kharkiv, she made friends with a woman who had just returned from Svalbard. Her friend told her of the beauty of the archipelago that Julia grew curious and wanted to see the place. In May 2019, she started working as a seamstress for the Russian mining company Trust Arktikugol and got to know Sergey and many other young people from Russia and Ukraine.

Two years on, she also moved to Longyearbyen. She wanted to do something new, to develop. Now, she works as a seamstress for the local company Systua i Nord – the Norther Seam Room.

Photo Montage

Sergey Chernikov puts in place the photo montage showing the different realities in Russia and Ukraine

Saved a premature baby

When Julia woke to the news that Putin had launched a war on Ukraine, she woke her boyfriend up and told him to make sure his parents were still alive. They live in Luhansk, in the Ukrainian part of the area, yet near what was the then-Russian-controlled border.

“They were alive and trying to stay positive. Now, they live in the basement of their house, though his father sometimes goes out to buy bread. That is all he can get hold of now”, she says.

Julia’s parents died when she was small, however, she has a lot of friends in Kharkiv with whom she has been in touch since the war started. The men took wives and children to the Moldovan border before they went back themselves to work as volunteers. Some get hold of supplies, others cook, and they transport people from Kharkiv to safer places.

These are the friends who are to get the funds raised at the exhibition.

“I believe in a clear blue sky. Now, schools and kindergartens are bombed. Several hospitals are destroyed. I fight for children. The money is to benefit them”, Julia says.

The day after the opening of the exhibition she sent the first money to two of her friends. They thanked and sent her a report that they had just been able to save a premature baby and its parents by getting them out from Kharkiv and to safety. The next day, they were to return to Kharkiv. They were to bring humanitarian aid in and then bring people out to safer areas.

“These are small, good news for me”, Julia says.

This article was originally published in Norwegian and has been translated by HNN's Elisabeth Bergquist.