Russian Crude Oil Now Flowing To China Via Arctic Ocean

Gazprom’s Novy Port oil terminal in the Russian Arctic. (Source: Gazprom)

Russia continues to reroute oil previously destined for Europe to Asia. Now, two tankers have traveled across the Arctic to China, thereby elevating the risk profile of Arctic shipping, experts say. Increased traffic means increased probability of an accident – with very high consequences.

With the onset of the summer navigation season on the Northern Sea Route (NSR), Russia has begun sending crude oil shipments to China via the Arctic. After an initial trial voyage in November 2022, energy analysts expect Russia to send regular shipments through the Arctic during 2023 and beyond.

With Europe completely out of the picture as a result of sanctions, Russia now diverts parts of its Arctic production to China. Additional shipments are destined for India.

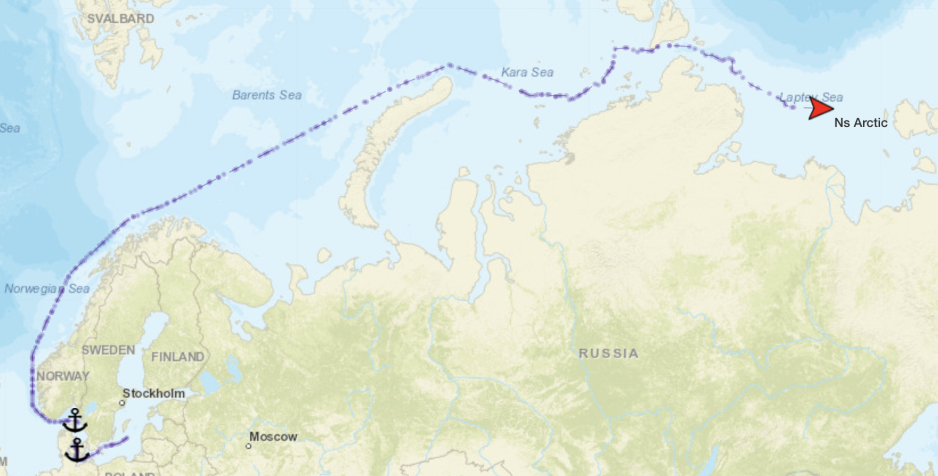

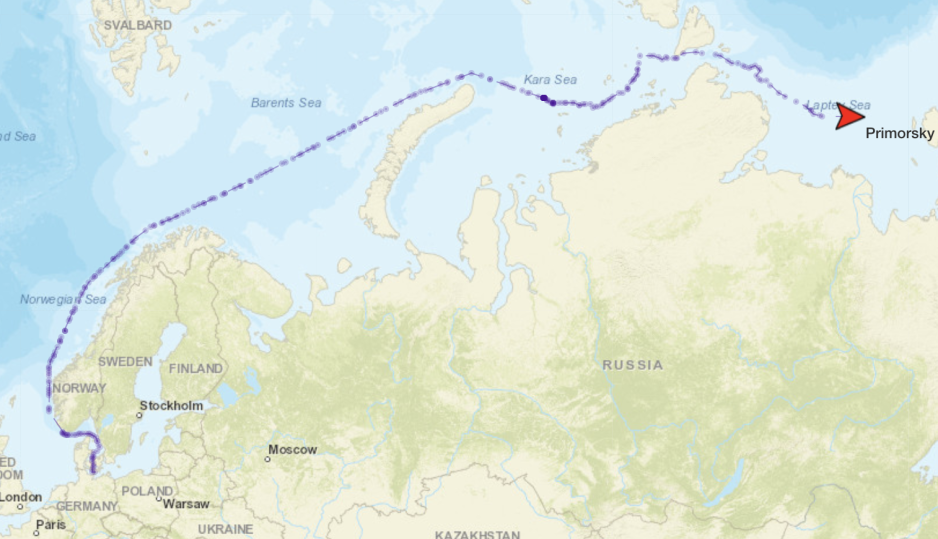

Two initial shipments departed from the Primorsk and Ust-Luga oil terminals near St Petersburg on 12 July and 13 July, passing through the Baltic Sea and up the Norwegian coast lines.

The two Aframax oil tankers, NS Arctic and Primorsky Prospect, each carrying around 730,000 barrels of crude oil, traveled along the NSR throughout the second half of July and are expected to arrive in Rizhao, China in mid-August.

Compared to the traditional route through the Suez Canal, the Arctic shortcut is around 30 percent faster. In November 2022 the tanker Vasily Dinkov traveled from near Murmansk also to Rizhao in around four weeks.

The NSR will be key to diverting the flow of crude oil away from Europe and toward Asia. With the massive Vostok oil project slated to open next year, the amount of crude oil being shipped via the Arctic will increase rapidly.

Until recently the NSR had seen less than a handful of oil shipments to Asia over the past decade.

Oil tanker NS Arctic in the Laptev Sea on 30 July 2023. (Source: MarineTraffic)

Pivoting to the East

The pivot to the East in terms of the flow of exports of oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) was always planned by the Russian government, says Matt Sagers who specializes in Russian energy at S&P Global, a research and analysis company.

“This process is now being pushed harder with the loss of the European market for Russian oil and the re-orientation of oil exports to “East of Suez”. Use of the Northern [Sea] Route reduced the number of days at sea and therefore the number of tankers (and overall capacity) that is required to move oil eastward. Entire upstream developments, like Vostok Oil, are intended to be evacuated via the route,” explains Sagers.

And the overall volumes will likely expand quickly given the availability of suitable vessels.

“According to our records, Russian state-owned tanker company - Sovcomflot (SCF) alone owned over 35 ice class tankers above 70,000 dwt. There is more tonnage in operation, with varied ownership,” says Svetlana Lobaciova, Senior Market Analyst at E.A. Gibson, an international shipbroker.

Oil tanker Primorsky Prospect in the Laptev Sea on 30 July 2023. (Source: MarineTraffic)

Shipping crude oil elevates risk

Shipping crude oil via the Arctic, compared to LNG, coal, or general cargo, significantly increases the risk profile for the region, experts say.

“Overall, increased traffic increases the probability of an accident occurring in this region, and the consequences would be very high,” says Mawuli Afenyo, Professor for Maritime Business Administration at Texas A & M University, who has conducted extensive research on oil spills in the Arctic.

Oil spills in ice-covered waters add a whole new level of complexity to the problem, Afenyo says.

“Oil spills in open water are already complex and difficult, with far-reaching impacts. It becomes even more complex when the oil spills in ice-covered waters, because the oil could get encapsulated in ice, get in between leads, and spill on snow in some cases.”

Oil encapsulated in ice can then quickly travel significant distances before the ice melts and the oil gets released into the ocean.

“This means an oil spill can occur at one point, but the effects could be felt many miles away,” Afenyo emphasizes.

Also read

In terms of cleaning up oil spills in ice-covered waters, burning the oil in place has been identified as the most effective and often only option, with serious environmental impacts.

Environmental organizations also warn against further fossil fuel exploration in the region.

“New fossil fuel production projects in the Arctic pose additional risks to Arctic ecosystems, species and communities that have been already impacted by rising temperatures,” explains Dr Sian Prior, Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance, a coalition of 20 non-profit organizations working to protect the Arctic.

The region’s remoteness and lack of infrastructure will also increase the response time, prolonging the time the oil remains in the water.

“Remote and harsh Arctic conditions means long spill response clean-up times, with accidents ruining local ecosystems for decades,” cautions Prior.

China taking advantage of new reality

Meanwhile, China stands to benefit from Russia’s pivot to the East as it continues to expand its energy imports, primarily LNG and crude from the Arctic.

In 2022, Russia surpassed Saudi Arabia as China’s largest supplier of oil. In total, China spent $58bn on oil imports from Russia in 2022, a figure that is likely to grow larger this year. In addition, it purchased $8bn of LNG from Russia, primarily from Novatek’s Yamal LNG plant in the Arctic.

Last year Russia sent around 35 percent of its oil exports to China, up from 31 percent in 2021.

On average, China pays $7 less per barrel for Russian crude oil than it pays for products from other countries. Analysts say that Chinese refineries have been able to use the western ban on Russian crude oil to their advantage in price negotiations with Russian sellers.

“As Moscow is no longer able to sell its fossil fuels in Europe, Asia has become a vital partner for Russian energy trade, with China at the head of the line,” explains Marc Lanteigne professor and researcher in politics, security and international relations at the University of Tromsø.

“Beijing has also successfully been able to negotiate bargain prices for these shipments, helpful at a time when China is still recovering from its post-Covid economic disruptions,” he continues.

While Chinese support of Russia’s energy ambitions has limits – in May President Xi Jinping did not publicly endorse the development of the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline – it appears committed to take receipt of fossil fuels delivered via the NSR.

“It is highly likely that Beijing will continue to take advantage of a window of opportunity to import more oil and gas from Russia as European markets remain closed,” concludes Lanteigne.