New Report: China is in the Arctic to stay

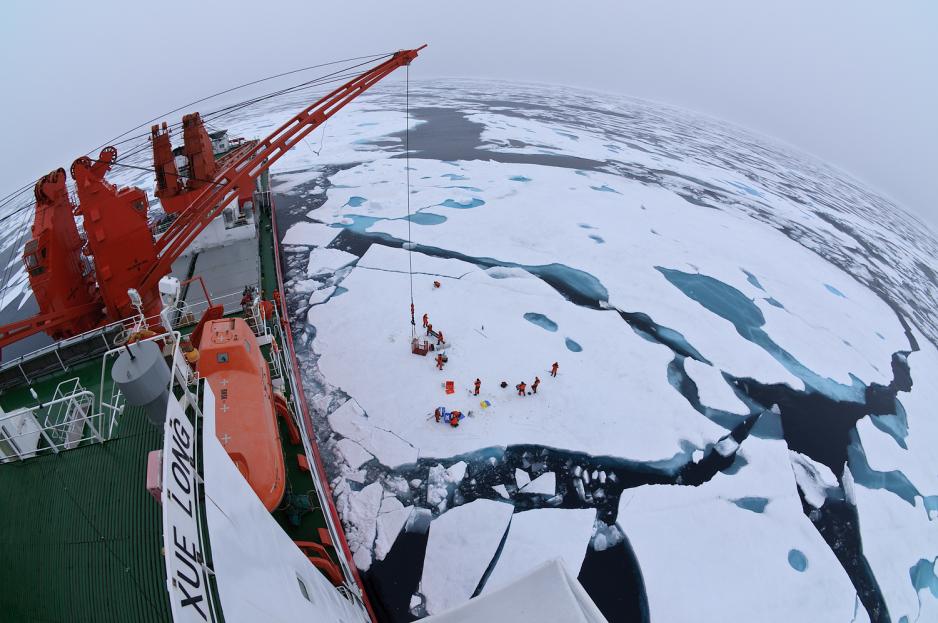

Drift ice camp in the middle of the Arctic Ocean as seen from the deck of the Chinese icebreaker Xue Long. (Photo: Timo Palo/Creative Commons)

China is now strong enough to be a ‘norm maker’ or even a ‘shaper’ in Arctic affairs, a new report on China in the Arctic finds.

High North News talked to some of the report’s authors: Timo Koivurova, Liisa Kauppila, Sanna Kopra, Marc Lanteigne, Mingming Shi, Matgorzata (Gosia) Smieszek, and Adam Stepien.

HNN: What are your new findings concerning China's current and future role in the Arctic?

Timo Koivurova: We have mapped out China’s increasing presence in the Arctic, both in policy and practise. This has in itself been a great contribution since China’s presence is increasing in the region in numerous ways: The vast investments in Arctic science, increasing commercial activities in different parts of the Arctic, and the awareness in China that the country contributes a lot to the environmental problems of the Arctic.

Marc Lanteigne: It is becoming evident that China is developing greater confidence in its Arctic diplomacy, but is still taking a cautious approach to its economic diplomacy in the region, especially as the Belt and Road plans in the region are starting to encounter pushback. China-Canada relations have deteriorated considerably in recent months, and Beijing’s relations with Sweden have also been problematic. Some Arctic states are expressing concerns about Huawei, and some plans such as the facilities at Arkhangelsk and the possible train link between Kirkenes and Rovaniemi, have yet to get off the ground. However, while the Arctic will not be a focal point for Chinese strategic interests, the region is still an important component in the country’s foreign policy.

HNN: What are general opportunities and risks of China as an Arctic actor?

Timo Koivurova: China is becoming a global power and in order to continue to develop along those lines, it requires a presence in regions considered strategically significant, including the Arctic. However, there has been the tendency to draw linkages between other areas where Chinese policy has conflicted with other states, such as the South China Sea, and Beijing’s Arctic policies. However, one needs to be careful about over-interpreting these links.

In our view, even if some scholars perceive hard security threats from China, we think that many reasons speak against it – the presence of powerful states with also powerful Arctic identities, lack of on the ground knowledge of the region, and large media, expert, and scholarly scrutiny over whatever China does in the Arctic. So we do think that China has chosen a conservative, non-revisionist multilateral multi-layered approach for the region, also recognizing the importance of the sovereignty of the eight Arctic states. It is important, of course, to bear in mind that China is a global power. Thus, it is important to continue scrutinizing its actions, but this is very much what the Arctic states have been doing – all investments from China that appear strategically threatening, seem to be also treated as such.

Expects more soft than hard power

Liisa Kauppila and Sanna Kopra: In contrast to various China threat theories, we did not take it for granted that China’s growing Arctic engagement would pose some kind of threat to the region’s future. At the same time, however, we found it necessary to identify potential risks that may emerge from the exercise of different types of power.

In general, the use of Chinese hard power does not seem a very plausible scenario. A military conflict of any scale would simply breed mistrust and thus hamper China’s chances of utilising Arctic economic opportunities. Forms of soft power, such as panda and science diplomacies, play an important role in China’s efforts to increase its leverage in Arctic affairs. In this way, China pursues to cultivate positive public sentiments that are needed if the country wishes to make large-scale investments in Arctic countries.

Beyond soft and hard power, there is a range of instruments of influence. To describe some of them, we use recently proposed the concept of sharp power. There is a fine line between soft and sharp power. The use of sharp power is equally seeking to shape public opinion but with much more questionable tools, such as censoring displeasing views and spreading deceptive information. Such instruments have become more important with the onset of globalisation and digitalization. In our view, being aware and critically assessing these risks - be they more or less likely - creates a solid foundation for long-term Sino-Arctic collaboration.

Marc Lanteigne: What makes the Arctic distinct is that its geography does not lend itself well to overt competition, since it is very difficult for any one power to be revisionist without inviting a response from the other main actors. At present, the politics of the Arctic lends itself to cooperation rather than rivalries, but that may not be the case in the future, especially if the region continues to become internationalised and viewed as an economic frontier.

Adam Stępień: Arctic cooperation is about awareness-building, developing common understanding of challenges, and acquiring sensitivities to Arctic issues. As China becomes an actor in the Arctic, and takes part in Arctic cooperation, there is also a chance for Chinese officials to acquire these sensitivities and common understandings. This is crucial as China has a major environmental footprint on the Arctic.

China influences the Arctic already

The country has economic weight and interests that already influence Arctic economies, in both direct and indirect ways. China also takes part –increasingly actively – in shaping international norms, and many international norms to a great extent are highly relevant for the Arctic (consider, for instance, the law of the sea, the Polar Code provisions within international shipping conventions, and the current negotiations regarding protection and management of biodiversity in the high seas). There are further possibilities that China contributes to the scientific understanding of the changing Arctic.

Gosia Smieszek: China has set a goal of becoming a world-class innovator by 2050. Thus, the country’s spending on research and development has been steadily growing over the past decades, exceeding all other counties together. China’s massive investments in R&D are also reflected in its advancing polar capacities.

Whereas the economic crisis in 2008 forced other countries to cut or suspend their R&D, China has been steadily developing its polar assets and potential. Consequently, in light of the extremely high costs of operating and conducting scientific research in the North, China’s role as a vital scientific partner might be expected to continue growing along the country’s improving innovation capacities.

HNN: How does China impact Arctic people?

Mingming Shi: Chinese companies and financial institutions have resources that allow them to become important investors in many Arctic regions. The Chinese government has a high degree of influence over Chinese economic actors, especially those owned or controlled by the state. The close interaction with Chinese officials in the Arctic context may be valuable for example for indigenous peoples if their communities are adversely impacted by Chinese companies or Chinese-funded investments.

Beijing has made quite a few declarations of respect for Arctic societies, cultures, and legal systems as well as its commitment to a win-win approach. These commitments provide guidelines for Chinese investment in the Arctic. Furthermore, the region might regard said guidelines as informal standards in order to examine Chinese engagement. At the very least, that opens an access point for dialogue with Chinese authorities and Chinese corporate management.

HNN: How is China’s changing role in global matters related to its developing role in Arctic affairs? Is the Arctic "special" for China in any respect or is it "just another region" in China's strategy towards more global influence?

Mingming Shi: China has been developing its policies on both the Antarctic and the Arctic fo quite a while already. In other words, China is not a newcomer in Polar affairs. However, even though it joined the Svalbard Treaty in the 1920s, the footprints of Chinese scientific research, political ties, and economic diplomacy have only appeared in the Arctic over the past few decades.

For the country, the Arctic is not just part of the larger blueprint of its global affairs; it is also an arena it has to play in with particular caution. For example, some Chinese officials and diplomats have expressed their views that the country should bear in mind the importance of Arctic affairs, given its special natural and political atmosphere.

Marc Lanteigne: The Arctic is definitely part of Beijing’s moves towards more effective cross-regional diplomacy, but unlike other regions outside of the Asia-Pacific, including Africa and the Middle East, China has a limited history in the far north, and has no geographic, historical, or ideological ties to fall back on when developing its Arctic diplomacy. Therefore, China has had to construct its Arctic regional identity much more carefully, in a way which both assures Arctic players that Beijing is not seeking a revisionist agenda, but also avoiding the ‘blueberry pie problem’ of the Arctic being cut up amongst the region’s eight players, with non-Arctic states being left out.

As well, although China has stressed that its interests in the Arctic are more long term as compared with other regions, the country cannot afford to be left behind, especially should a scramble for northern resources take place. The extension of the Belt and Road into the Arctic, even if no concrete projects appear right away, is nonetheless the main way in which Beijing is seeking to define itself as an indispensable Arctic partner.

China wants to shape norms

The other issue here is not so much rules but rather norms. China used to be a ‘norm taker’ starting in the 1990s, allowing the West to set the agenda and to develop post-cold war organisations, since Beijing was in a weaker power position and needed the goodwill of many global regimes in order to re-integrate into the international system. However, China is now strong enough to be a ‘norm maker’ or even a ‘shaper’, and does not want to be strictly bound by US and Western institutions. Beijing is now in a position to influence global norms, especially with the United States potentially withdrawing from much international discourse. The question is: How will Beijing use its new capabilities in the Arctic?

Sanna Kopra: After President Trump announced to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement, the world has hoped for China to step up and fulfil the leadership vacuum in international climate politics left by the US. Although President Xi Jinping has responded positively to these expectations and China has strong domestic incentives to take the findings of the recent IPCC report very seriously, it has not demonstrated any kind of climate leadership role in the Arctic. In my view, taking a stronger leadership role in international efforts to tackle climate change would not be a big sacrifice for China. Conversely, such a leadership role would support China’s national interests and alleviate various China threat theories at the global level. When it comes to the Arctic, China’s stronger commitment to tackle climate change would probably improve the state’s image and generate trust amongst the Arctic states. This would, in turn, help China to legitimize its stronger engagement in Arctic regional affairs.

HNN: Building on your findings concerning China's current and future role in the Arctic, which implications thereof do you see for Arctic countries' policies?

Timo Koivurova: We tend to think that China is here to stay, and its scientific and economic presence will increase with possible hard security implications – Arctic states should remain watchful of those engagements, as they have mostly done by this day. It is also important to understand that China is a great power, and economic dependence on it is not always a good thing.

What we are now seeing is a further diversification of China’s Arctic interests, including in political, economic, legal, and scientific areas. Now that the White Paper has been published, China will be under further pressure to demonstrate what specific roles it will play in the region.

Concerns about Chinese influence and control

Adam Stępień: A part of our report focuses on concerns related to stronger Chinese presence in Arctic Finland and enhanced cooperation with Chinese actors as regards Arctic questions (for instance, commercialisation of Finland’s Arctic expertise towards Chinese Arctic activities). We have identified a couple of dimensions of these concerns.

First, there is the risk that stronger ties lead to increased Chinese future economic and political influence at national and regional levels, leading to dependence, greater possibilities to exert political pressure, and increased exposure to downturns in Chinese economy.

There are concerns related to Chinese control of strategic infrastructure, including recent controversies around a port investment in southern Sweden or the planned upgrade of Greenlandic airports. Chinese mining companies in Canada were allegedly complaining about lengthy community consultations processes and complex stakeholder engagement requirements. That may not bode well for the social performance of Chinese economic actors in the regions where impact assessments, benefit sharing, and stakeholder participation have been greatly advanced in the last couple of decades.

Second, there are anxieties about the environmental and social performance of Chinese economic actors. These anxieties stem to a great extent from the experiences of Chinese investments in other regions like Africa and South America.

Third, there are also questions as regards the reliability of Chinese investors, as many plans tend to be announced, creating hopes, concerns and first social impacts, but then ultimately many plans are abandoned, leaving behind a high degree of disappointment.

These concerns have so far not materialized in Arctic Finland, at least not to a significant degree. Interestingly, while some actors in Finland are concerned about the rising presence of China in the Finnish Arctic, others are actually disappointed that there is so little Chinese investment. These contradictory perspectives coexist in Finnish public debate at present.

China denied land acquisition

However, some problematic cases do occur in other Arctic regions and they tend to have circumpolar resonance. For instance, we had some cases of planned major land purchases by Chinese investors in Greenland, Iceland, and Norway – all of them not coming to fruition due to local and national resistance based on both socio-environmental and security grounds.

Authorities and other actors in the Arctic need to be aware of risks related to any foreign investments. However, on the other hand it is important that we do not treat China as a unified monolithic actor, which behaves the same way in all regions and circumstances. There are different companies, different state agencies, different academic institutions and it is not wise to put all of them in a black box called China. Decision-makers should consider each case of Chinese presence in the region against specific circumstances and nature of this presence.

Marc Lanteigne: Arctic countries need to take the broader political context into consideration in their handling of China. Although President Xi has consolidated his power, and is now able to retain the post of president indefinitely, China is now facing serious economic headwinds as well as an emerging trade war, which could further exacerbate the various divisions within the Chinese government. This may especially effect the question of whether to continue the Belt and Road Initiative in its present form and what the speed for further economic reforms should be.

Arctic countries need to understand China

Liisa Kauppila: Arctic countries should dedicate more resources for increasing their understanding of China as a global economic actor, including Chinese actors’ modes of operation and business culture. Language skills in Mandarin Chinese, in particular, should be improved through consistent efforts. This is particularly important for the small Nordic Arctic countries since China is now becoming the new influential neighbour with whom we must learn to coexist in a productive manner.

Gosia Smieszek: Not only is China among the world’s leading science powers but it also has the world’s largest education system with a stated goal to increase both incoming and outgoing student mobility – another area worth further exploration by Arctic, and in particular Nordic, countries.

Sanna Kopra: Arctic countries should also intensify scientific cooperation with China on black carbon – the issue area that has been strongly promoted as a platform for enhanced cooperation among states also by Finland’s President Sauli Niinistö. Due to the lack of knowledge on black carbon emissions and their sources at the domestic level, China has not taken an active role in the Arctic Council’s work on black carbon.

Although China’s air quality policies do not explicitly address black carbon, its efforts to improve air quality and public health by decreasing coal burning are very important for the future of the Arctic, too. Improved scientific knowledge of black carbon inventories and links between climate change, air quality, and public health are necessary for China’s stronger involvement on international cooperation on black carbon.

Professor Timo Koivurova is a director of the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland.

Liisa Kauppila is a China scholar and futurist at the Centre for East Asian Studies of the University of Turku.

Sanna Kopra is a postdoctoral researcher at the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland.

Marc Lanteigne is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Tromsø - The Arctic University of Norway.

Mingming Shi is a Master's student of West Nordic Studies at the University of Iceland in Reykjavík, and a Project Manager for the journal Icelandic Times.

Margorzata (Gosia) Smieszek is a political scientist at the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland.

Adam Stępień is a political scientist at the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland.